News/Reports

Ecological Reserves management issues gap Analysis Survey -2021

PDF version: ER Management Issues Gap Analysis Summary update Feb 15 2021

Citation: Feick, Jenny L. Jan. 2021. Ecological Reserves Management Issues Gap Analysis

Summary January 2021 Update. Victoria, B.C., Friends of Ecological Reserves, unpublished

report.

Acknowledgements: This report and the data analysis that supports it were prepared by

Jenny Feick and Ian Hatter with assistance from Marilyn Lambert and Louise Beinhauer,

and information from Mike Fenger, Garry Fletcher, Stephen Ruttan and Rick Page.

About the Friends of Ecological Reserves (FER) This volunteer-based, not-for-profit

charitable organization raises awareness and promotes the interests of ecological reserves

in British Columbia (B.C.). FER works to promote and support scientific research,

monitoring and reporting in and around ecological reserves, volunteer wardens and the

stewardship function within existing ecological reserves, and the nomination, assessment

and establishment of worthy new ecological reserves. FER educates the public and

government agencies regarding the significance of ecological reserves, the values they

contain, and the threats they face. FER welcomes new members. Find more information at

the FER website (see https://ecoreserves.bc.ca/about-friends/ ) and in issues of the FER

newsletter, the Log (see https://ecoreserves.bc.ca/news/newsletter-archive/ ).

The Friends of Ecological Reserves recognizes and respects the First Nations within whose

traditional territories ecological reserves exist. FER acknowledges that much of British

Columbia remains unceded land and appreciates the graciousness of the Indigenous hosts

in areas containing ecological reserves. Even though the B.C. Ecological Reserves Act does

not explicitly address traditional Indigenous use of ecological reserves, FER supports it as

long as it does not destroy the values for which the reserve was established. Reconciliation

may provide opportunities for additional ecological reserves identified by traditional

Indigenous knowledge keepers for their Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) values.

On April 2, 1971, the Government of British Columbia became the first jurisdiction in

Canada to pass legislation to protect ecological reserves. May 4, 1971 is the date of the

first Order in Council stemming from that Act to legally establish the first 29 ecological reserves.

The spring of 2021 marks the 50th anniversary of the Ecological Reserve Act. Although the

BC government has established 154 ecological reserves, it transferred six to other

government jurisdictions in the early 2000s, so the current number of reserves in B.C. is

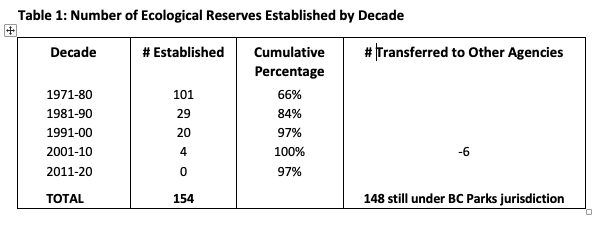

148. The BC government has not established any new ecological reserves since 2009.

Photo on Front Cover: A view of part of the extensive Garry oak ecosystem in the 390-ha

Mount Maxwell Ecological Reserve (ER # 37) on Saltspring Island, South Coast Region,

April 1, 2019 (Photo by Jenny Feick)

Photo on Back Cover: Trail through the 7.5 ha Honeymoon Bay Ecological Reserve (ER

#113), Vancouver Island, South Coast Region, April 17, 2016 (Photo by Jenny Feick)

Feick)

1.0 Introduction

On May 4, 1971, the Government of British Columbia became the first jurisdiction in Canada to pass legislation to protect ecological reserves. May 2021 marks the 50th anniversary of the Ecological Reserve Act and regulations and the establishment of B.C.’s first ecological reserves. No new reserves have been established since 2009 and the 2005 assessment of the condition of existing reserves raised “concerns that the ecological values of many individual reserves are at significant risk and a more proactive approach to managing the reserves is required to reverse this trend.” (FER 2006)

Despite FER’s periodic communications with BC government agencies about worthy candidates, no new ecological reserves have been added as of 2020 and from the reports of volunteer wardens, the state of existing reserves continues to deteriorate. At their November 2019 meeting, the Board of the Friends of Ecological Reserves (FER) decided to make a renewed and concerted effort to encourage BC government officials to establish several new ecological reserves and to address management, conservation and stewardship issues in existing ecological reserves in time for the 50th anniversary of the Ecological Reserves Act. FER developed the precursor to this report (and the spreadsheet containing the data used to inform it) to provide background information for a meeting on June 3, 2020 with BC Parks focused on improving the management, conservation and stewardship of existing ecological reserves. This update was prepared to help inform discussion at the next meeting on January 19, 2021 and further refined afterward.

2.0 Methodology

In the spring of 2020, six Board members researched specific information on the BC Parks and FER websites to inform development of an Excel spreadsheet. Information sought included the presence of approved management planning direction documents, the dates of each, and management issues identified in them; the existence, dates and topics of scientific research papers and monitoring reports on the FER website; the existence of ER warden reports on the FER website, which ERs currently have wardens, and whether FER has contact information for them. Ecological reserve wardens described current issues in emails, phone calls or in person. FER members Louise and Fred Beinhauer provided additional information. Rike Moon and Marilyn Lambert collaborated in 2020 to update the information on which ERs have active wardens with current volunteer contracts. Garry Fletcher provided content for a new section on special considerations for marine ERs. For both the original report and the January 2021 update, Ian Hatter led the data entry, quality control and analysis of the spreadsheet data. Jenny Feick wrote the original and updated report based on the original and updated data analysis.

——————————————————————————-

[1] Friends of Ecological Reserves. 2006. State of British Columbia’s Ecological Reserves Report for 2005. See https://ecoreserves.bc.ca/2006/12/04/state-of-bcs-ecological-reserves-report-for-2006/

[2] Garry Fletcher, ERs#1-25, Mike Fenger ERs#26-50, Jenny Feick, ERs#51-75, Steve Ruttan, ERs#76-100, Rick Page, Ers#101-125, and Marilyn Lambert, ERs#126-154.

[3] Gary Backlund & Katharine Banman, Jim Borrowman, H & J Calson, John Field, Paul Linton, Diane Moran, Rosamund Pojar, Bev & Bill Ramey, Harold Sellers, Amanda Vaughan, Gerry Van der Wolf, and Ken Willies.

———————————————————————————1

3.0 Establishment Date and Location of Existing ERs in B.C.

The Government of British Columbia established most (66%) of its 154 ecological reserves between 1971, the year it enacted the Ecological Reserve Act, and 1981. Ninety-seven percent of the ERs were established by the year 2000. Since 2001, six ERs were transferred to other agencies and four new ERs were established. Det San is the most recently established ER (2009). No ERs have been established since then.

To help implement the International Biological Program, Dr Vladimir Krajina proposed the concept of ecological reserves to the BC government in the late 1960s. He led the scientific work that informed the development and passage of the Ecological Reserve Act by April 2, 1971. His oft-stated goal for the Ecological Reserves System was to protect one per cent of B.C.’s land area in ecological reserves.

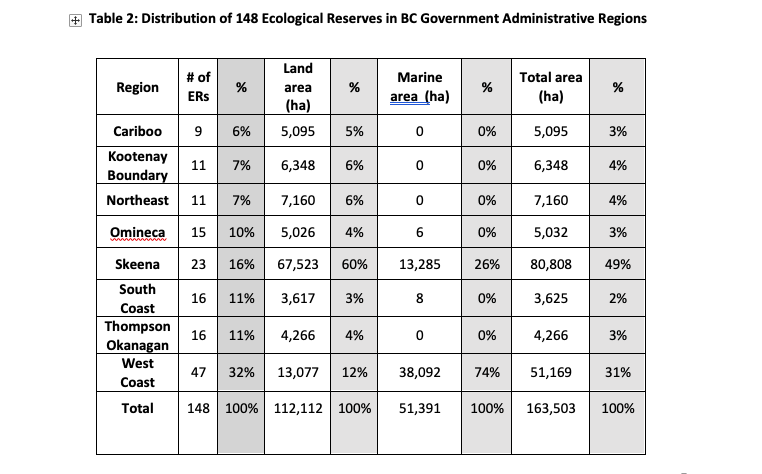

The total area for all ERs established by the BC government was 112,632.75 ha. In the mid-2000s, the BC government transferred 521 ha to other agencies with the six ERs it gave away, leaving 112,111.75 ha. With 88.7 million ha of Crown land in the Province of British Columbia, the amount set aside in protected areas comprises 14.2 % (Government of British Columbia 2011). Legal constraints on timber harvesting provide additional protection leading some government officials to claim that 17% of B.C.’s Crown land is protected. Small in size, the land and marine foreshore area protected by the 148 ERs still under provincial jurisdiction comprises 0.13% of B.C.’s Crown land base.

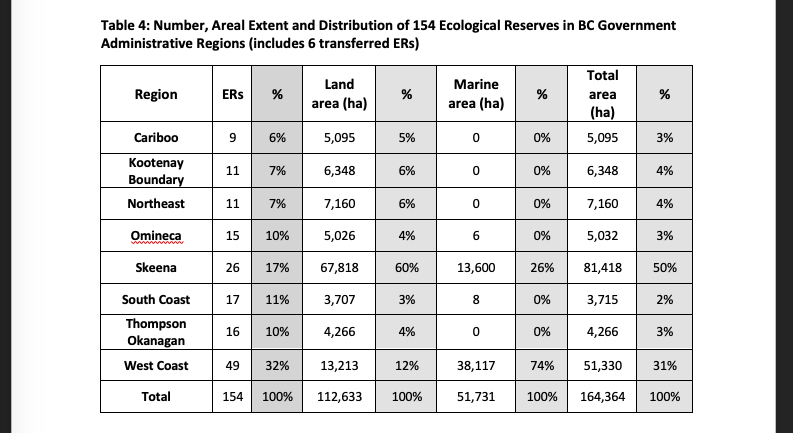

Table 2 on the following page contains the number of current ERs in each region, their areal distribution figures on land and marine foreshore (in ha) with percentages of the total. The figures for the original 154 ERs appears in Table 4 in Appendix A.

———————————————————————————————

[1] See https://ecoreserves.bc.ca/2012/03/12/contributions-of-vladimir-krajina-to-ecological-reserves-in-bc/

[1] See https://bcparks.ca/about/park-designations.html#ers

—————————————————————————————-2

4.0 ER Management Planning Direction Gap Analysis

4.1 ERs with No Management Planning Direction

Out of 154 ERs, 22 (14%) have no management planning direction listed on the BC Parks or FER websites. Of these, six are ERs that BC Parks no longer manages. In the mid-2000s, the BC government transferred five ERs to Parks Canada. ER #74 (UBC Endowment Lands/Pacific Spirit) in the South Coast Region went to Metro Vancouver Regional Parks.

Of the remaining 148 ERs still under BC Parks jurisdiction, 19 (13%) still require management planning direction. Thirteen of the remaining ERs have Overviews so some of the information needed to inform management planning was assembled. However, given the age of these documents, additional updating is needed to adequately inform plans.

———————————————————————————–

[7] Three in the Skeena Region went to Gwaii Hannas National Park Reserve (#44 – East Copper/Jeffrey/ Rankine Islands, #95 – Anthony Island, and #96 – Kerouard Islands) and two in the West Coast Region went to Gulf Islands National Park Reserve (#121 – Brackman Island and #15 – Saturna Island).

[8] ER #3 Soap Lake, ER #6 Buck Hills Road, ER #8 Clayhurst, ER #20 Columbia Lake, ER #21 Skagit River Forest, ER #47 Parker Lake, ER #116 Katherine Tye, ER #131 Stoyoma Creek, ER #133 Gamble Creek, ER #147 Grayling River Hot Springs, and ER #154 Det San.

—————————————————————————————3

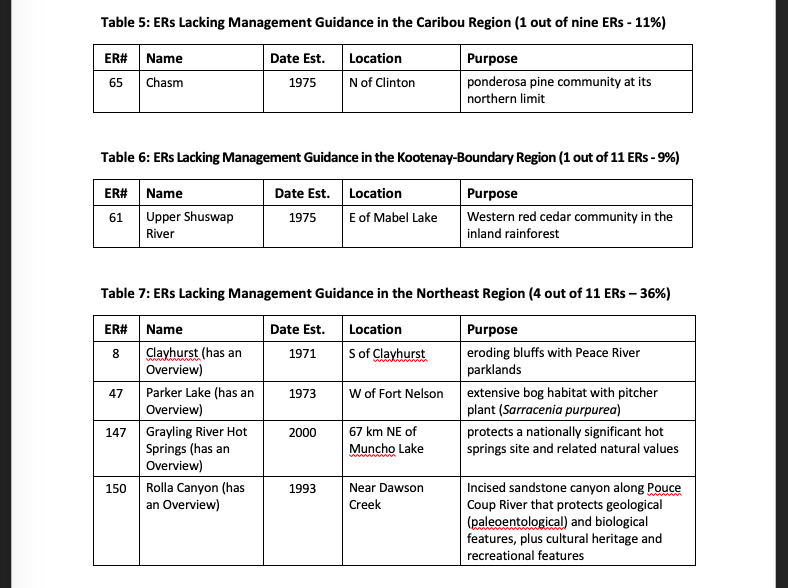

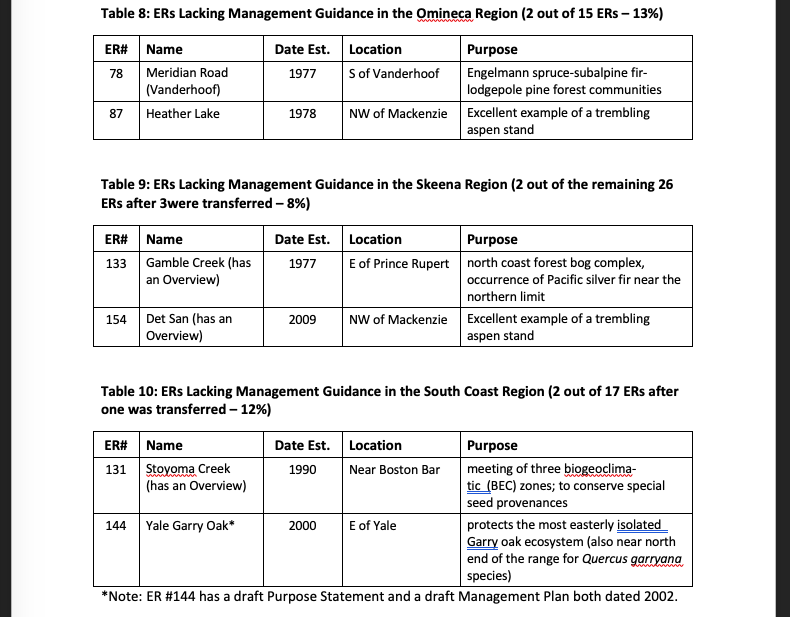

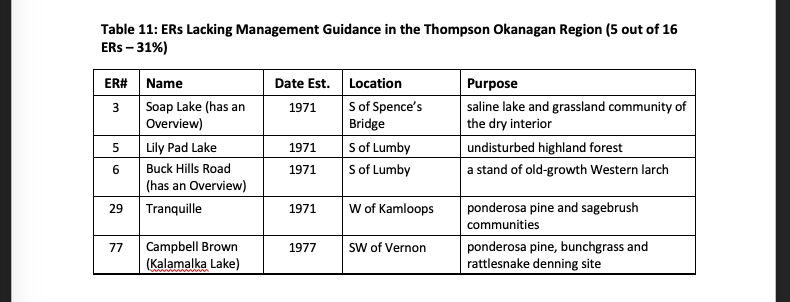

The list below identifies the ERs in each region that have no management planning direction recorded on either the BC Parks or FER websites (See also Appendix A). The West Coast Region is the only region that has management direction for all remaining ERs. The majority of the gaps are in the Thompson Okanagan and North East regions. While Det San, the newest ER (established in 2009), is among those that lack any management planning direction, 13 of the 18 ERs or 72%) with no management planning direction were established in the 1970s (see Appendix A).

Thompson-Okanagan Region: #3 (Soap Lake), #5 (Lily Pad Lake), #6 (Buck Hills Road), #29 (Tranquille), #77 (Campbell Brown)

North East Region: #8 (Clayhurst), #47 (Parker Lake), #147 (Grayling River Hotsprings), #150 (Rolla Canyon)

Skeena Region: #133 (Gamble Creek), #154 (Det San)

Omineca Region: #78 (Meridian Road), #87 (Heather Lake)

Cariboo Region: #64 (Ilgachuz Range), #65 (Chasm)

South Coast Region: #106 (Skagit Rhododedrons), #131 (Stoyoma Creek), 144 (Yale Garry Oak)

Kootenay Boundary Region: #61 (Upper Shuswap River)

West Coast Region: All remaining ERs have some management direction.

Many of the 12 ERs with management plans approved in the 1990s no longer appear on the BC Parks webpages for those ERs and can only be found using links on the FER website. This suggests that BC Parks no longer considers the previous management direction for these ERs valid. Thus, these gaps in ER management planning also need to be addressed.

4.2 ERs with Purpose Statements

Purpose Statements are four-page documents that describe the roles of a particular ecological reserve, briefly list management issues, answer basic conservation, scientific research, recreation and management information in a checklist format, and provide the date of establishment and area of land and foreshore included in the reserve. They provide very little in terms of management direction. Preparation of these documents does not even appear as a step on the management planning process outlined on BC Parks’ website.

——————————————————————–

[9] ER #106, Skagit Rhododendrons, has a one-page management statement dated 1990 with no approval page that must be used “in conjunction with the descriptive text and map pages supplied in the ‘Guide to Ecological Reserves in British Columbia’” (Ministry of Environment, Lands, and Parks 1992, see https://ecoreserves.bc.ca/1992/11/15/guide-to-ecological-reserves-in-bc/ ).

[10] ER #144, Yale Garry Oak, has a draft Purpose Statement and a draft Management Plan, both dated 2002, so much of the work has been done and it should be fairly easy to update.

[11] The approval dates for management plans for the following ERs are in the 1990s: #9 Tow Hill (1999), #10 Rose Spit (1999), #17 Canoe Islets(1990), #18 Rose Islets(1990), #48 Bowen Island (1990), #76 Fraser River (1990), #88 Skwaha Lake (1996), #89 Skagit River Cottonwoods (1990), #92 Skahist (1996), #99 Pitt Polder (1990), #110 McQueen Creek (1996), and #117 Haley Lake (1995).

——————————————————————————4

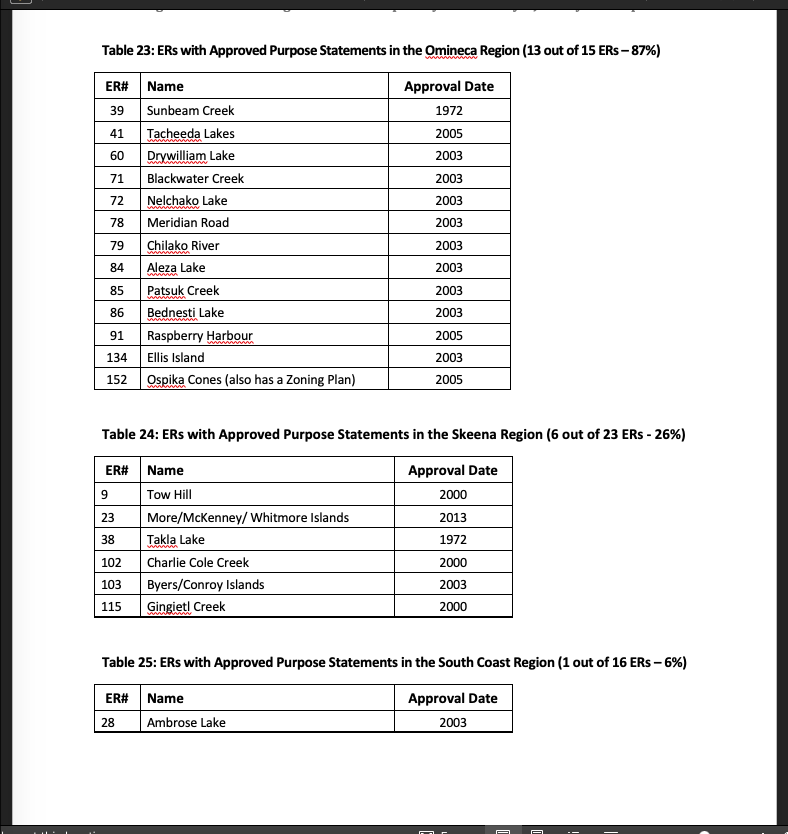

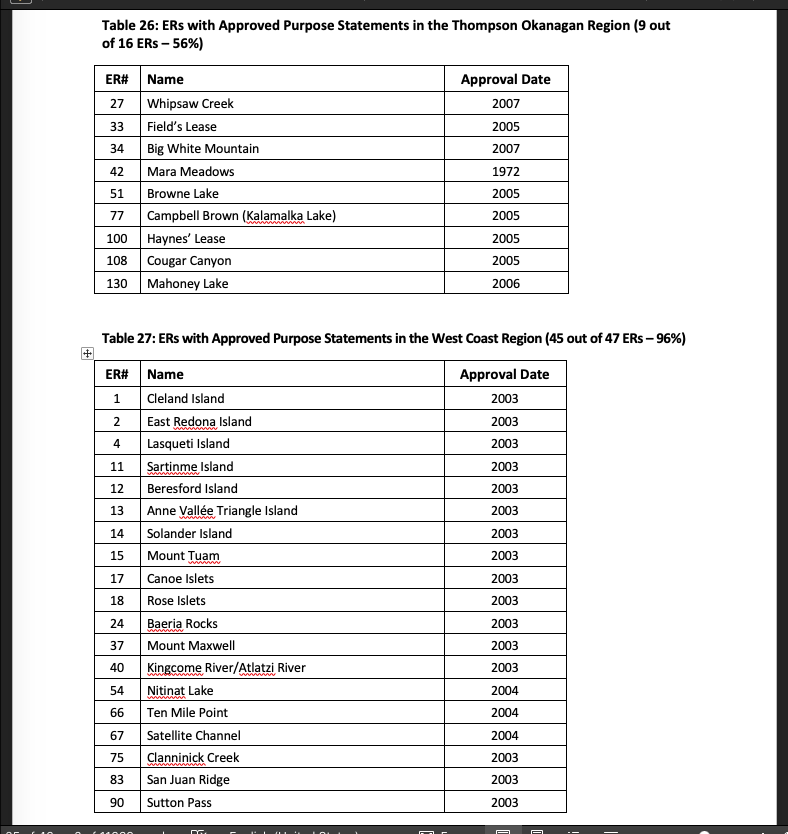

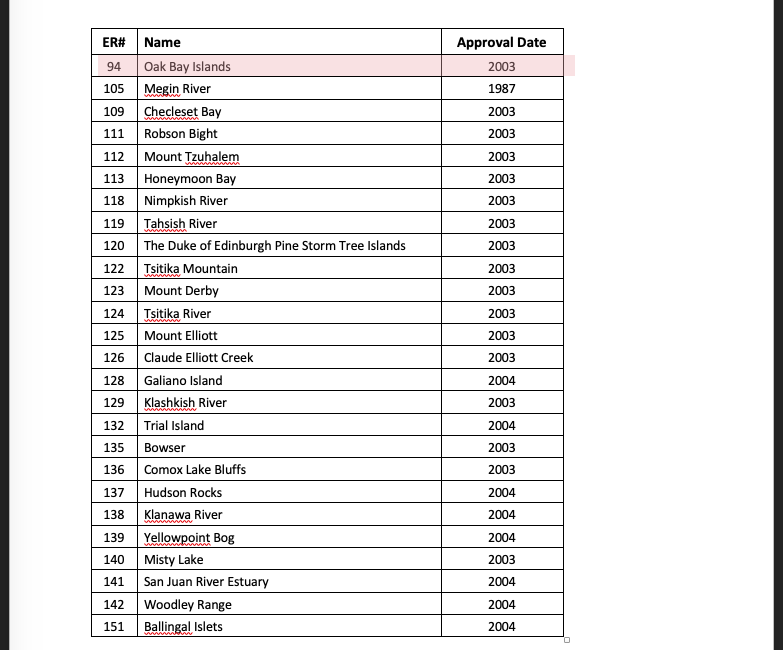

Ninety-four ERs (63%) have approved purpose statements on the BC Parks website. The range in dates for when these purpose statements were approved is 1972-2013, with several in the 1980s, 1990s and early 2000s. The Purpose Statements for four ERs have been superseded by other management planning documents, including those for ER #38 (Takla Lake), ER #102 (Charlie Cole Creek), ER #104 (Gilnockie Creek), and ER #115 (Gingietl Creek). See Appendix C for the details.

ERs with purpose statements lack the level of direction and guidance provided by management direction statements or management plans.

4.3 ERs with Management Plans or Management Direction Statements

Forty-eight (32%) of the 148 ERs managed by BC Parks have approved management guidance in the form of management plans (29) or approved management direction statements (19) posted on the BC Parks website. The range in dates for when these management guidance documents were approved is 1990-2017, with many in the period 2002-2004 (when Nancy Wilkin was ADM of MoE). Management direction for the following ERs is imbedded in the planning documents for other protected areas: ER #9 (Tow Hill), ER#10 (Rose Spit), ER #64 (Ilgachuz Range), ER #68 (Gladys Lake), and ER #153 (Francis Point). Four of the ERs with approved management plans also have Overview documents, including ER #20 (Columbia Lake), ER #21 (Skagit River Forest), ER #22 (Ross Lake), and ER #116 (Katherine Tye). See Appendix B for the details.

“A management plan is a document that outlines the vision and direction for a protected area. This will include direction on the types, location and threshold of uses and activities appropriate within different parts of a protected area including appropriate levels of visitor use and facility development. A management plan is the result of a management planning process and is developed with First Nations, local governments, the public and other interest groups.” (BC Parks website – https://bcparks.ca/planning/).

Only twenty percent (29) of the ERs currently have approved management plans. The most recent of these is the Mackinnon Esker Ecological Reserve Management Plan, approved in 2017 (see https://bcparks.ca/eco_reserve/macesker_er.html). Most of the plans were completed in the early 2000s or in the 1990s. The BC Parks website no longer provides links to the older documents. For example, nothing shows up under management planning on the BC Parks website for ER #92, Skihist except the message, “Online management planning information for this Ecological Reserve is not available at this time”. The only way to see the Management Plan for Skihist Ecological Reserve approved in November 1996 is via the FER website links – https://bcparks.ca/planning/mgmtplns/skihist_er/skihist_er_mp.pdf?v=1610484264695

Although a management plan for Skihist Provincial Park was approved in 2018, it contains nothing on the ER.

—————————————————————————-5

An additional 13% (20) of ERs have management direction statements. The following description appears in most of these documents.

“Management direction statements (MDS) provide strategic management direction for protected areas that do not have an approved management plan. Management direction statements also describe protected area values, management issues and concerns; a management strategy focused on immediate priority objectives and strategies; and, direction from other planning processes. While strategies may be identified in the MDS, the completion of all these strategies is dependent on funding and funding procedures. All development associated with these strategies is subject to the Parks and Protected Areas Branch’s Impact Assessment Policy.”

While not full management plans, these shorter documents contain enough useful information to provide management direction for ecological reserves. Unlike the older management plans produced in the 1970s through 1990s, they include issues such as First Nations interests and climate change, which gained greater attention in the 2000s. The Skeena Region has the majority of the management direction statements for ERs.

5.0 Monitoring and Research Reports and Other Information on ERs

FER attempts to provide corporate memory for the system of ecological reserves in British Columbia by acquiring and maintaining a repository of information about each ER on its website. This resource is made freely available to researchers and the public to facilitate the use of ERs as living laboratories to study environmental change. The inclusion of monitoring and research reports in ERs plays a key role in this effort. In addition, the FER website also includes links to BC Parks monitoring protocols, BC Parks iNaturalist Project images and other photographs, maps, ER warden reports, and various unpublished and published reports and articles about ERs. Each ER has its own webpage on the FER website with categories such as Warden Reports, Management Issues, Research Archive, Reports, Photos, iNaturalist Photos, Species Lists, and All reports for this site.

5.1 Monitoring Reports

Out of the 148 ERs still managed by BC Parks, 48 (32%) have some type of monitoring report listed on the FER website. Sixty-eight percent of the ERs (100/148) have no monitoring reports listed on the FER website. The FER website still shows monitoring reports for the ERs that were transferred to other government agencies.

The date range for the most recent monitoring report for a particular ER is 1971-2020. The median date is 2000. The average is 1997. The most common topics of these most recent monitoring reports are the results of surveys of: vertebrate fauna, especially birds, vegetation (vascular, non-vascular plant species), management issues/state of the ER, ecology/general natural history, invasive plants, hydrology, invertebrates, marine environment and wildfire impact.

————————————————————————————–6

5.2 Research Reports

Out of 148 ERs still managed by BC Parks, 45 (30%) have research reports listed on the FER website. The FER website still contains links to research reports for the ERs that were transferred to other government agencies. Seventy percent of the ERs (103/148) have no research reports listed on the FER website.

ERs have served as study sites for numerous Masters theses and PhD dissertations, which are listed in the Research Archive section on the applicable ER webpage on the FER website. One of many examples includes the 1992 University of California PhD dissertation in Biology, Social Dynamics of Male Killer Whales, Orcinus orca in Johnstone Strait, British Columbia, by Naomi Anne Rose, which focused on Robson Bight (ER #111). Many relevant articles in peer-reviewed journals, textbooks, and unpublished research reports have resulted from studies in particular ERs. Anne Vallee Triangle Island (ER #13) has spawned over 35 papers from Simon Fraser University and more than 20 from other institutions.

ERs have provided opportunities for significant longitudinal research. For example, research on the Drizzle Lake ecosystem started in 1975. The University of Victoria’s Dr Tom Reimchen, the principle researcher, says “a conservative estimate of the research investment is between $120,000 to $150,000 in the Drizzle Lake ER” (#52). Another is the research on the demography of Vancouver Island marmots centered on Haley Lake (ER #117). The Royal B.C. Museum and the B.C. Conservation Data Centre use ERs as study sites for biodiversity and species at risk. For example, the Williams Creek (ER #114) serves as a study area for dragonfly diversity, range, and distribution.

The date range for the most recently posted research report for an ER is 1976-2015. Research that took place prior to the enactment of the Ecological Reserve Act in 1971, often informed why certain sites became ERs and some of these studies are noted on the FER webpages for individual ERs. For example, IBA research for many of the seabird colonies on the coast extends back to 1951 and the first study of yellow pine took place in 1961 at what became ER#27, Whipsaw Creek in the Thompson Okanagan Region. The median date for the most recent research report posted on the FER website is 2002. The average is 1998. Recent research includes innovation applications of LIDAR technology at ER #84 (Aleza Lake) near Prince George in the Omineca Region and how climate change affects phenology in ER # (Bowser) on Vancouver Island in the West Coast Region.

6.0 ER Wardens

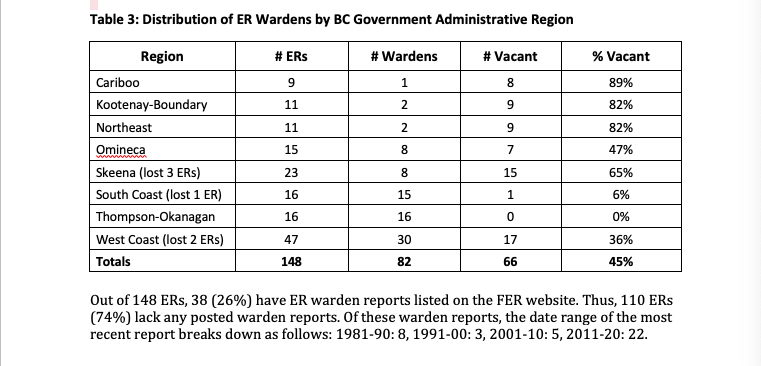

In 2020, BC Parks and FER worked together to reconcile their respective lists of volunteer ER wardens. An analysis of the resulting list revealed the following information. Of the 148 ERs still managed by BC Parks (six having been transferred to other agencies), 81 (55%) have ER wardens. Some wardens look after more than one ER. There used to be volunteer wardens at the five reserves that were transferred to Parks Canada and the one transferred to Metro Vancouver.

—————————————————————————————-7

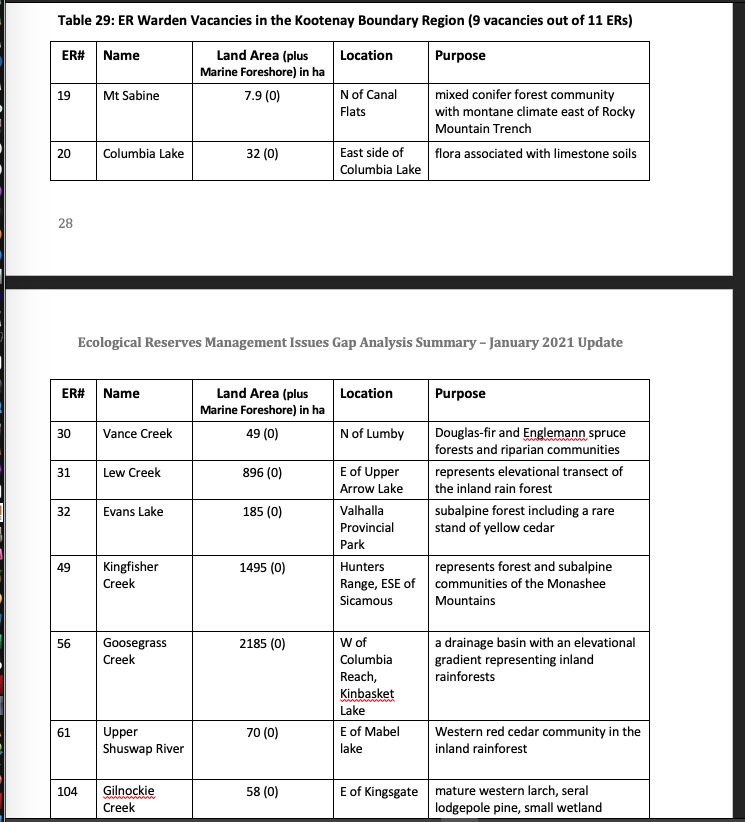

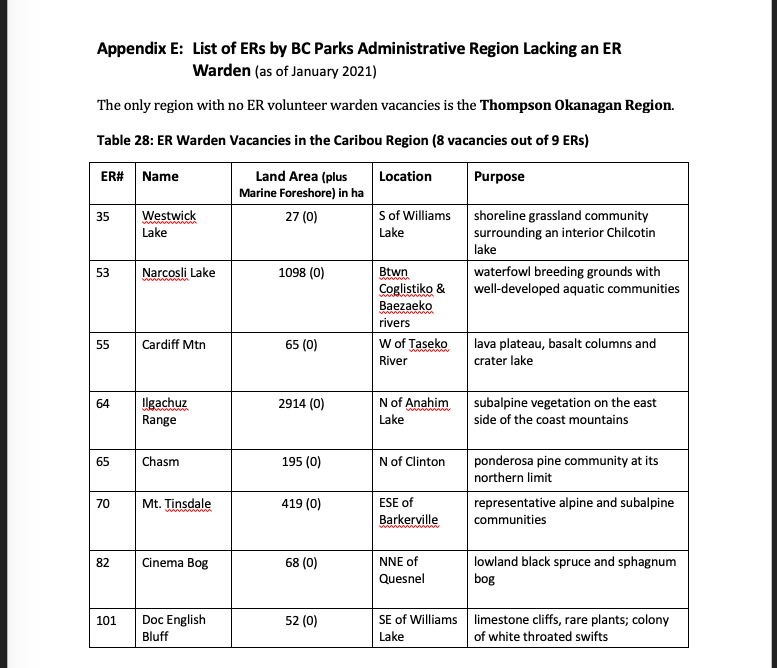

Sixty-seven of the 148 ERs (45%) have vacancies in ER warden positions. Although Columbia Lake ER #20 is included among the ERs with a vacancy, BC Parks and the Ktunaxa Nation are discussing the Ktunaxa taking on the stewardship of this reserve.

FER has contact information for ER wardens at 61 (41%) of the existing 148 ERs still managed by BC Parks. BC Parks has contact information for wardens with whom they have a current active contract at an additional 21 ERs (14%). The contact information can only be provided to FER by the individual warden due to federal and provincial privacy laws. Thus 14% of the current volunteer ER wardens do not receive FER’s newsletter, (called The LOG), or other information and support from FER.

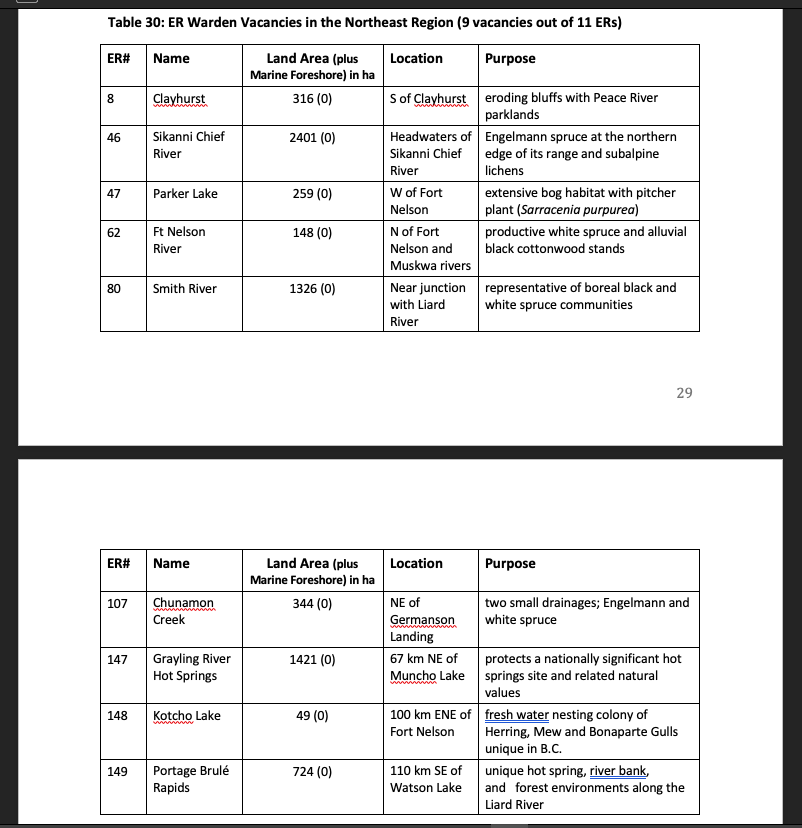

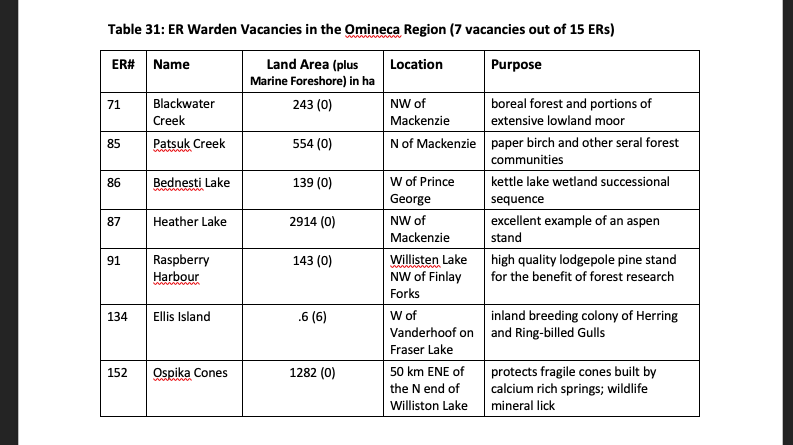

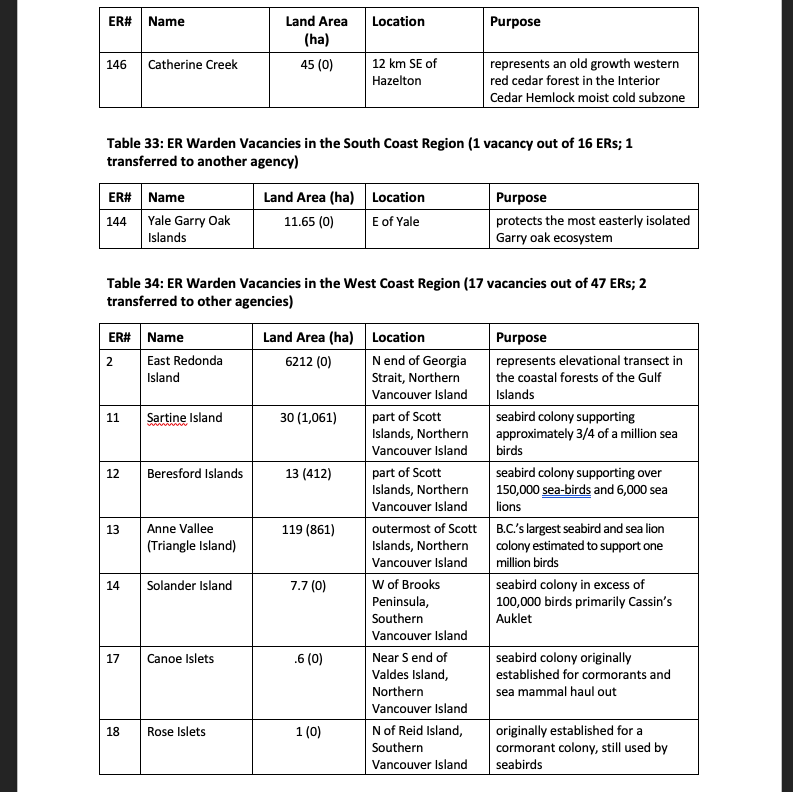

Table 3 displays the regional distribution of ER wardens. The Thompson Okanagan remains the only region with no vacancies. Despite the larger number of ERs in the West Coast Region, just six percent are vacant. However, nearly 90% of the ERs in the Caribou Region have vacancies and over 80% of the ERs in both the Kootenay Boundary and Northeast regions have vacancies. Skeena has 65% of its ER warden positions vacant, the Omineca has 47%, and the West Coast 37%. Skeena and the Northeast regions have smaller overall human populations, less road access, and vaster distances. Some of the vacancies in other regions are in ERs with extremely challenging access. Creative solutions, including collaborations with Indigenous and other partner organizations, could ensure the warden’s stewardship function in these areas.

————————————————————–8

7.0 Management/Conservation/Stewardship Issues in Existing ERs in B.C.

7.1 Management/Conservation/Stewardship Issues in Management Planning Documents

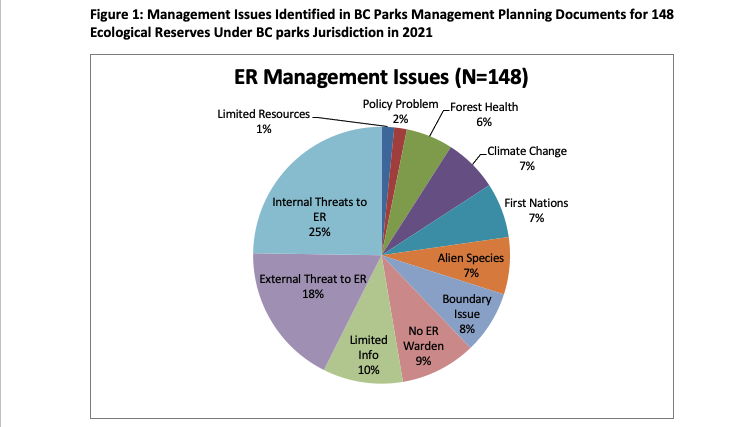

In most cases, management planning documents listed on the BC Parks website contain a section that identifies management issues for the ecological reserve. In some cases, the ER is included with an adjacent protected area with no issues identified for the ER. Issues fall into eleven categories. Ten issues were ranked based on the number of times they were identified in ER management planning documents. One category (no ER warden) was updated based on January 2021 data. For the 148 ERs under BC Parks jurisdiction, Figure 1 shows the relative number of times issues were identified in BC Parks management planning documents. The top five are internal threats, external threats, limited information, boundary issues and alien species, followed closely by First Nations issues and climate change. Limited resources and policy problems were occasionally mentioned.

Issue #1 (mentioned 172 times) Internal Threats: Examples of internal threats included inappropriate activities, i.e. recreational use such as illegal camping, hunting, trapping, cattle grazing, physical trespass and vandalism, access and damage from linear developments like roads, railways, transmission lines, and pipelines. It is alarming how much commercial harvesting of shellfish, fish, trees for firewood, and non-timber forest products (mushrooms, moss, horsetails, salal, etc.) takes place in ERs and how many ERs get used as refuse dumps by local communities. Authorized visitor use was noted when numbers were high and increasing and damage (trampling of native plant species, disturbance of seabirds and other wildlife, erosion of or damage to sensitive geological features) was evident.

——————————————————————————————–9

Issue #2 (mentioned 124 times) External Threats: The most common external threats are adjacent developments, especially logging operations, urban development (residential subdivisions, expansion of water treatment plant), roads and other linear developments (hydro lines, transmission lines, pipelines, seismic lines), as well as disturbance from nautical (motor boats, canoes, kayaks, rafts) and air traffic (helicopters and airplanes), agriculture (primarily cattle grazing but also vineyards), mines, oil and gas developments, risk of oil spills on marine ERs, boat noise and effluent from commercial fishing operations and tourism operators, and recreational developments such as ski areas. It is sad to note how many ERs are now either tiny fragments of old-growth forest completely surrounded by clear cuts on Crown land or other natural vegetation communities ringed by private forest, urban, or agricultural land.

Issue #3 (mentioned 70 times) Limited Information: BC Parks planners identified as a significant issue the lack of baseline environmental data for an ER (natural features, plant and animal species inventories, species at risk surveys, plant communities, as well as hydrologic regimes) and the paucity of monitoring data. They also noted limitations in information about cultural and archaeological resources, particularly those of significance to First Nations. Visitor use data is also lacking in many ERs. There is little information about many ERs for use by BC Parks, other government agencies, First Nations, and the public. Information in most ER management planning documents is out of date (most documents were approved in 2003) and hence some information is no longer correct (i.e., usually, what was a potential threat of an adjacent development has now happened).

Issue #4 (66 vacancies) No ER Warden: While this was mentioned frequently in management planning documents as an issue, this number represents the actual number of vacancies in ER warden positions in January 2021 according to BC Parks records. Without an ER warden, there is virtually no stewardship or monitoring function in an ER. This greatly reduces the effectiveness of an ER in achieving its legislated purpose.

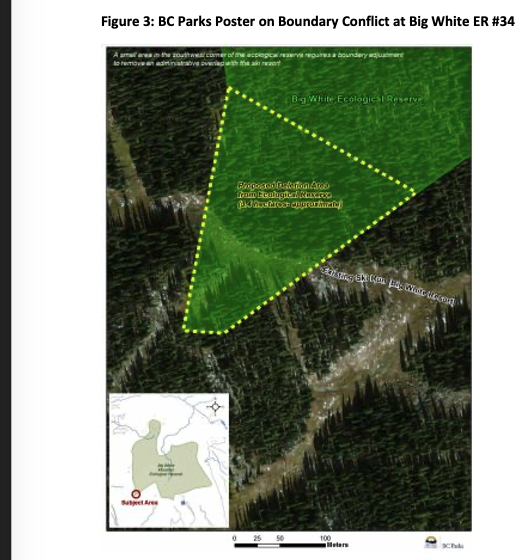

Issue #5 (mentioned 55 times) Boundary Issues: ER management planning documents tended to highlight the lack of boundary demarcation, the lack of signs around the border of the reserve, the decrepit state of fences, and the lack of mapped coordinates on brochures. The absence of posted notices promoting the ER’s values and level of protection was also cited. Several reserves identified that the boundaries need adjustment because of shifts in ER values related to natural fluvial and climate-change induced hydrologic, landscape and species range changes or because the size of the reserve combined with external threats renders it ineffective in protecting species at risk or other ER values. In a few instances, boundaries appear to be disputed by neighbouring landowners and trespass is an issue (e.g. Big White Ski Area incursions into the Big White ER). Disappointing to read is the lack of apparent awareness of the presence, location, and values of an ER, not only by members of the public, but also by BC government employees, resulting in authorization of non-conforming uses of an area (e.g. road development, trapping, and commercial hunting by guide-outfitters).

————————————————————————————–10

Issue # 6 (mentioned 50 times) Alien Species: Alien species within an ER are an internal threat resulting from the external threat of adjacent land use, and were separated out as a specific issue. Most of the times when alien species were mentioned, they were invasive plants. Specific examples included baby’s breath, broom, carpet burweed, dandelion, Himalayan blackberry, holly, hound’s-tongue, ivy, knapweed (diffuse, meadow, and Russian), long-spine sandbur, puncture vine, reed canary grass, sulphur cinquefoil, thistle (Canada and Scotch), toadflax (bastard and Dalmatian). However, a significant number of animal species were also identified. These included fish (introduced bass and trout), amphibians (American bullfrogs), and mammals. Cattle, feral goats and sheep, rabbits were among the domestic mammals identified. In certain ERs on small coastal islands, non-native rats and raccoons threaten native seabird populations. At ER# 52, Drizzle Lake, and near Haida Gwaii, non-native black-tailed deer consumed native vegetation and introduced beaver changed littoral environments supporting spawning areas for native sticklebacks.

Issue # 7 (mentioned 48 times) First Nations: First Nations issues encompass a broad range of topics such as opening up a conversation and establishing a relationship with First Nations in the vicinity of the ER, interest in ensuring Indigenous rights are respected, the need to conduct inventories of cultural resources of significance to First Nations and to document First Nations values and Indigenous use in an ER, the effect on the ER of land use decisions made by First Nations adjacent to it, co-management proposals and opportunities, and assertions from individual First Nations for the exclusive use of land, control of Indigenous archaeological resources, research permit process, and land-use.

Issue #8 (mentioned 47 times) Climate Change: Climate change was sometimes mentioned without elaboration and other times management planning documents described the specific effects of climate change on the ER. Of greatest concern were climate change effects on moisture regimes, hydrology, extreme events (winter storms, floods, drought, and catastrophic wildfire), sea level rise, and rising ocean temperatures, and the subsequent effects these environmental changes have on species survival, distribution, range, and ecosystem composition. Sometimes the issue was the lack of management direction to protect rare plants undergoing impacts from climate change. Several ERs set aside to protect specific species at the edge of their range appear to be ideally situated to study the effect of climate change on shifting distribution as climate envelopes move north and up in elevation in response to global warming. For example, Cinema Bog (ER #82) in the Cariboo Region is the most southern limit for that vegetation type. Sea level rise could eliminate the land portion of coastal island ERs.

Issue # 9 (mentioned 41 times) Forest Health: Mountain pine beetle infestations, effects of forest fire suppression (fuel build-up) and wildfire, shifts in species composition related to disruption to natural disturbance regimes, fire suppression, changed moisture regimes, warming climate, and tree removal comprised the main forest health issues mentioned.

While two issues were mentioned only 11 times each (tying for 10th place), they were nevertheless important in the context of a particular ER. The main Policy Problems noted were the adverse effects of the Initial (Wildfire) Attack and Fire Suppression policies on Forest Health, as well as decisions on non-conforming uses (usually linear development bisecting an ER) and ER boundaries being inadequate to safeguard biological features. Similar to Lack of an ER warden, Limited (BC Parks) Resources resulted in having little to no staff presence at the ER. The resulting lack of stewardship, monitoring, compliance and enforcement actions exacerbates internal and external threats, with negative consequences for the ecological integrity of the ER.

————————————————————————————–11

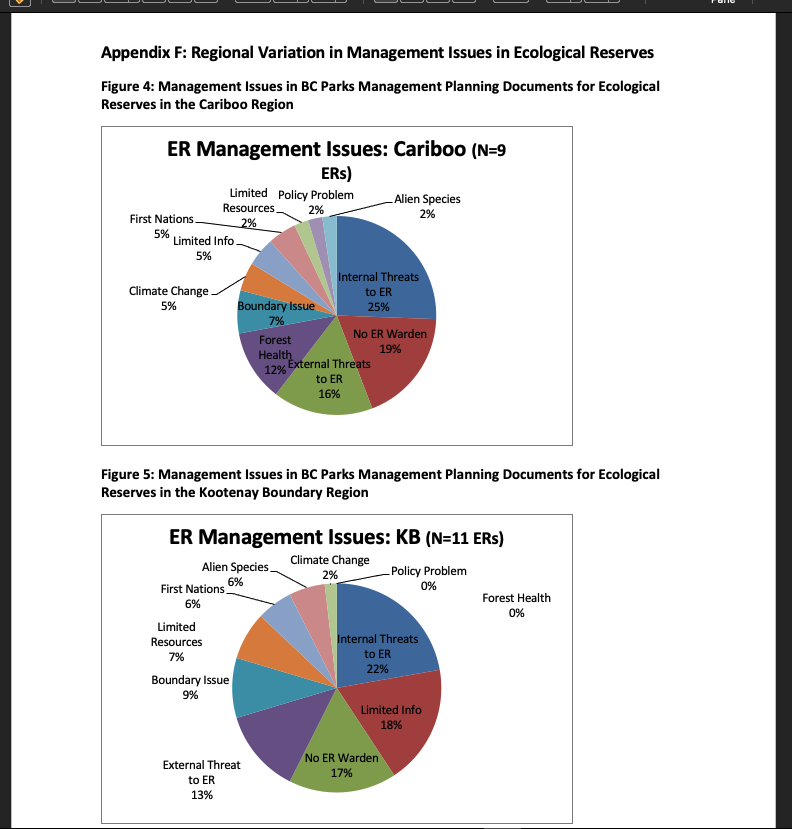

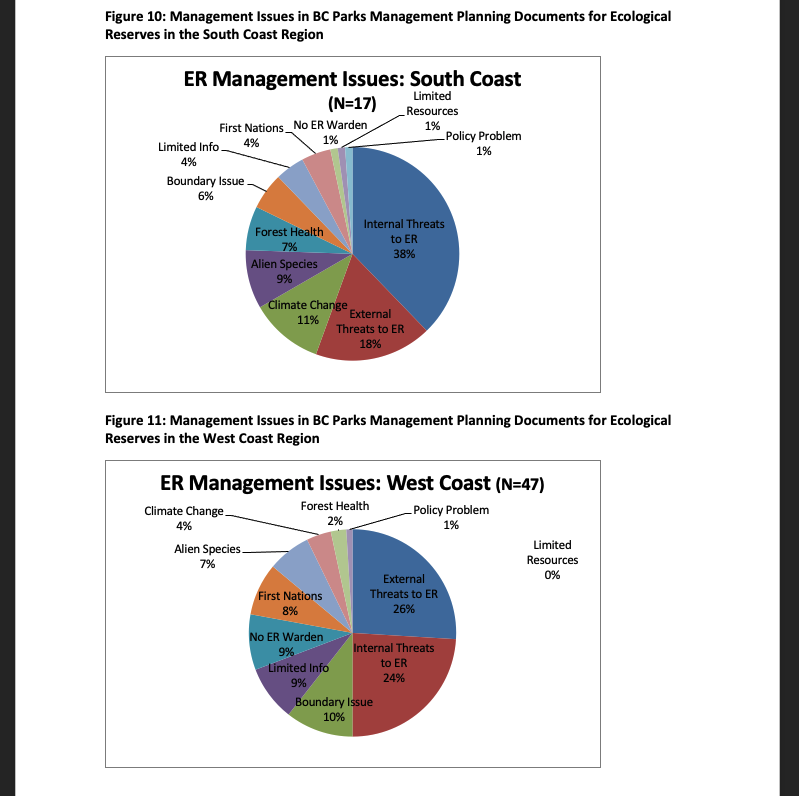

7.2 Regional Variations in Management Issues

Management issues varied across the administrative regions of BC Parks. Regional variations in management issues can be seen in Figures 2 to 9 in Appendix F.

While the management planning documents in most regions identified examples of internal threats as the primary issue facing ecological reserves, the West Coast identified external threats more often than internal threats and the Skeena Region identified limited information about their ecological reserves ahead of internal and external threats. In the Northeast Region the lack of volunteer wardens was just ahead of internal and external threats whereas this isn’t an issue at all in the Thompson Okanagan Region where all ERs have volunteer wardens. Forest health was the second most often mentioned issue in the Omineca Region and yet never mentioned in any of the management planning documents in the Kootenay Boundary Region. Alien species were the second most often identified issue in the Thompson Okanagan and yet never mentioned in the Northeast Region. Boundary issues was the third most frequently mentioned issue in the West Coast Region and was in the top five or six issues in all other regions. Climate change was the third most often mentioned issue in both the Omineca and South Coast regions but mentioned as an issue for one ecological reserve (ER#19, Mount Sabine) in the Kootenay Boundary Region. Issues related to First Nations interests and cultural heritage were mentioned most often in the management planning documents of the Skeena and the West Coast regions, and not at all in the Thompson Okanagan Region.

7.3 Current Management/Conservation/Stewardship Issues Identified by ER Wardens

From time to time, ER wardens contact FER to highlight important issues they face in the management, conservation and stewardship of the ecological reserve(s) they voluntarily care for. FER informed wardens with known contact information about the upcoming meeting with BC Parks and asked if they could identify their top three to five issues. These letters were collated and analyzed. The issues most mentioned in the communications (email, phone call, in person) received by FER between December 2019 and May 2020 include:

————————————————————————————-

[12] The collated letters were provided to the entire FER Board in June 2020 and to BC Parks in January 2021.

————————————————————————————12

- Boundary Issues (lack of defined boundaries, shifting boundaries, unmaintained fence and lack of signage, need for boundary adjustments or buffers to protect ERs from shifting boundaries due to natural processes and adjacent land use) – mentioned eight times

- Invasive Plants threatening natural vegetation – mentioned six times

- Issues with BC Parks – mentioned five times (lack of knowledge of the purpose of ERs, of natural and cultural resources in existing ERs), the need for better compliance and enforcement, specifically addressing the inability of rangers to issue tickets for violation of the Ecological Reserve Regulations, the need for more resources for BC Parks to support ERs; and improved transmission of monitoring information from BC Parks to volunteer ER wardens.)

- Internal Threats – mentioned four times (garbage dumping, tree cutting and other; vandalism, illegal camping; helicopter training landings and recreational fixed winged planes landings, shore use by Indigenous peoples and the public)

- External Threats: – mentioned three times (e.g., boat traffic, build-up of debris washing down from the upper road; feral domestic animals)

- Forest Health – mentioned three times (fire and pine beetle damage)

Other issues mentioned once include: Climate change effect on rare plants; the need for updated monitoring (e.g. an updated review of rubbing beach use by orcas)

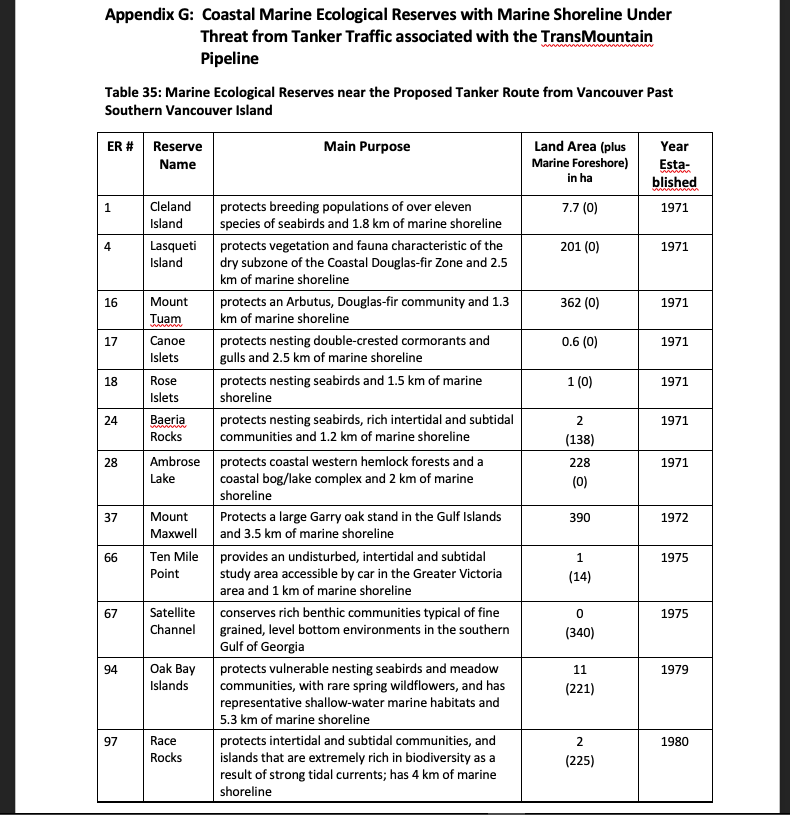

7.4 Specific Issues Identified for Marine ERs

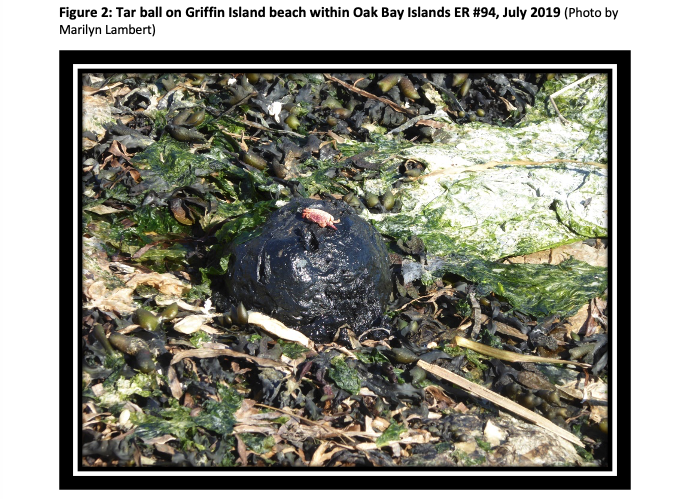

Oil pollution and petrochemical spills are already a significant external threat in marine coastal ERs (see Figure 2 on page 14). Proposed expansion of tanker traffic poses additional concerns.

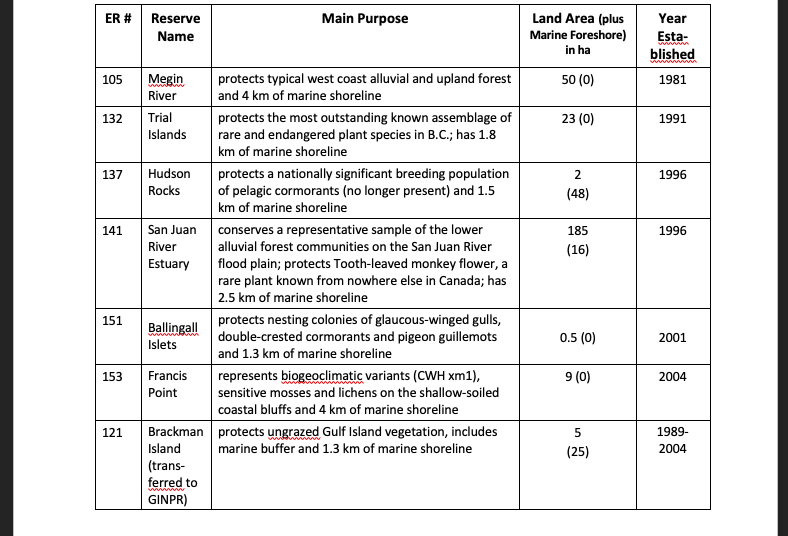

In April 2014, during the NEB Hearings for the Trans-Mountain Pipeline, FER was granted intervenor status. FER identified 19 coastal ERs that have marine shoreline along the proposed route of tankers from Vancouver past the southern part of Vancouver Island. One of the issues FER brought forward is the lack of contingency planning for those ERs with marine frontage in the event of a catastrophic oil spill. See https://ecoreserves.bc.ca/2018/12/06/neb-trans-mountain-reconsideration/. Sub-tidal and foreshore is not included as protected area in 11 of these coastal ERs. Nevertheless, a storm blowing against a shoreline will carry aerosols of hydrocarbons far inland as has happened in past oil spills. The main danger from any chemical spill is always at the interface of land and sea, and thus the spray zone is always vulnerable. In a 50-knot wind from the south west, most of Trial islands’ rare plants would probably be affected very badly, for instance. Since B.C. owns to the high tide zone of all their shorelines, any ER with marine shoreline can be adversely affected by an oil spill.

————————————————————————————

[13] These include Cleland Island (ER #1), Lasqueti Island (ER #4), Mount Tuam (ER #16) Canoe Islets (ER #17), Rose Islets (ER #18), Baeria Rocks (ER #24), Ambrose Lake (#28), Mount Maxwell (ER #37), Ten Mile Point (ER #66), Satellite Channel (ER #67), Oak Bay Islands (ER #94), Race Rocks (ER #97), Megin River (ER #105), Trial Islands (ER #132), Hudson Rocks (ER #137), San Juan River Estuary (ER #141), Ballingall Islets (ER #151), and Francis Point (ER #153), plus Brackman Islands (former ER #121), which was transferred to Parks Canada for the Gulf Islands National Park Reserve in April 2004. See details in Table 35, Appendix G, page 35.

[14] Cleland Island (ER #1), Lasqueti Island (ER #4), Mount Tuam (ER #16) Canoe Islets (ER #17), Rose Islets (ER #18), Ambrose Lake (#28), Mount Maxwell (ER #37) Megin River (ER #105), Trial Islands (ER #132), Ballingall Islets (ER #151), and Francis Point (ER #153).

————————————————————————————–13

During the time period of the NEB hearings on the TMX pipeline (2012-2019), the Western Canada Marine Response Corporation (WCMRC) plans excluded any reference to planning for the protection of sensitive coastal ecological areas such as ERs. Since then (2020/21), the WCMRC has produced plans with some level of mitigation for some parts of the ecological reserves and other sensitive ecosystems. (e.g., Race Rocks and part of the Oak Bay Islands ecological reserves). The reality is that there are a high number of days each year when deploying booms and oil capture techniques are impossible due to adverse weather conditions. This along with the presence of strong tides in some areas affects the vulnerability of the 19 marine ecological reserves to massive catastrophic impacts when an accident happens in the shipping lanes.

——————————————————————–14

7.5 Prioritized List of Management, Conservation and Stewardship Issues

FER recommends that priority be given to addressing the following issues in existing ERs:

1. Solve Boundary Issues, including confirming GPS coordinates, installing signs, repairing fences, removing alien species in areas adjacent to ERs, and addressing shifting natural boundaries (e.g. Fraser River ER #76, Katherine Wye ER #116, and San Juan Estuary ER #141). Addressing boundary issues helps address many internal and external threats to ERs.

2. Address Internal Threats, including trespass (building roads, dumping garbage), illegal activities (camping, hunting, harvesting shellfish, fishing, woodcutting, etc.) and removing invasive alien species (plants and animals)

3. Address External Threats by negotiating with the Ministry of Forests, Lands, Natural Resource Operations and Rural Development (FLNRORD) and other government agencies (federal, provincial, regional district, municipal) as well as organizations such as the Western Canada Marine Response Corporation (WCMRC), and private businesses (development corporations, logging companies, ski resorts, etc.) on mitigation measures to decrease adverse effects on ERs from adjacent development, including establishing buffer zones, replacing land deleted from an ER with an equivalent or greater amount of land, applying erosion-prevention techniques, sound barriers, etc.

4. Fill Information Gaps for specific ERs (species at risk, biodiversity, Indigenous interests, cultural resources, geological features)

————————————————————————————–15

5. Address First Nations Interests (explore co-management opportunities, rename ERs, document FN interests, values, cultural resources, recruit and support FN wardens/guardians

6. Enhance BC Parks Stewardship Actions (fill vacancies in volunteer warden positions, establish partnerships, monitoring & reporting, communications, information sharing, compliance & enforcement, complete management direction statements for ERs with no effective management planning direction, identify gaps in BEC representation in the ER system, meaningfully commemorate 50th anniversary of Ecological Reserve Act).

—————————————————————————————16

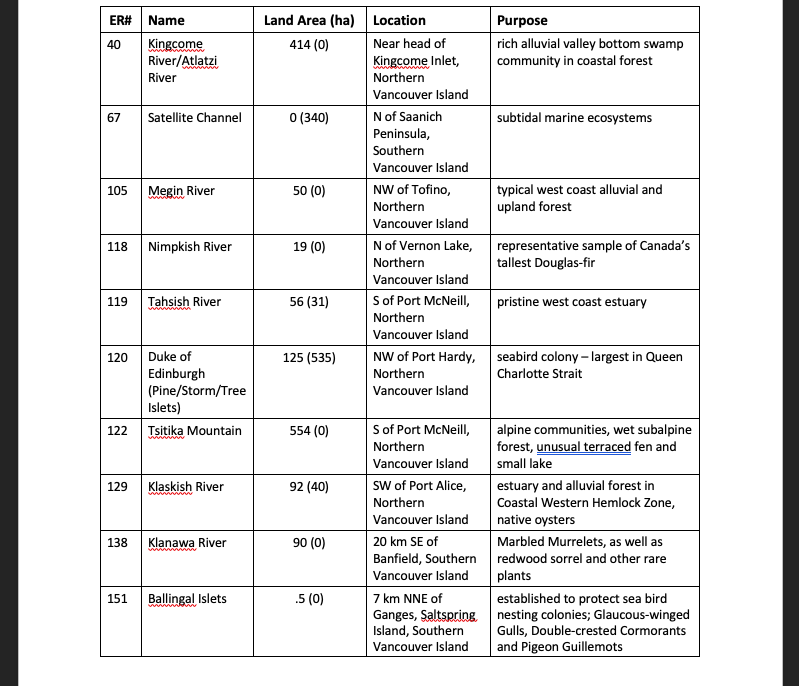

Appendix A: Distribution of All 154 Ecological Reserves by BC Government Administrative Regions

Nearly one-third of the original 154 ERs were established in the West Coast administrative region of the BC government. The Skeena Region had 17% of the ERs. The South Coast had 11%. The Omineca and Thompson-Okanagan each had ten percent, and the Kootenay-Boundary and Northeast regions each had seven percent. The Cariboo Region had six percent of the ERs in B.C. ERs that were transferred to other government agencies came from the Skeena, South Coast, and West Coast regions.

————————————————————————————17

Appendix B: List of ERs by BC Parks Administrative Region Lacking Any Management Planning Direction

The only region where BC Parks has some form of management direction for all of its existing ERs is the West Coast Region (two ERs were transferred to Parks Canada).

——————————————————————————–18

———————————————————————————19

———————————————————————————-20

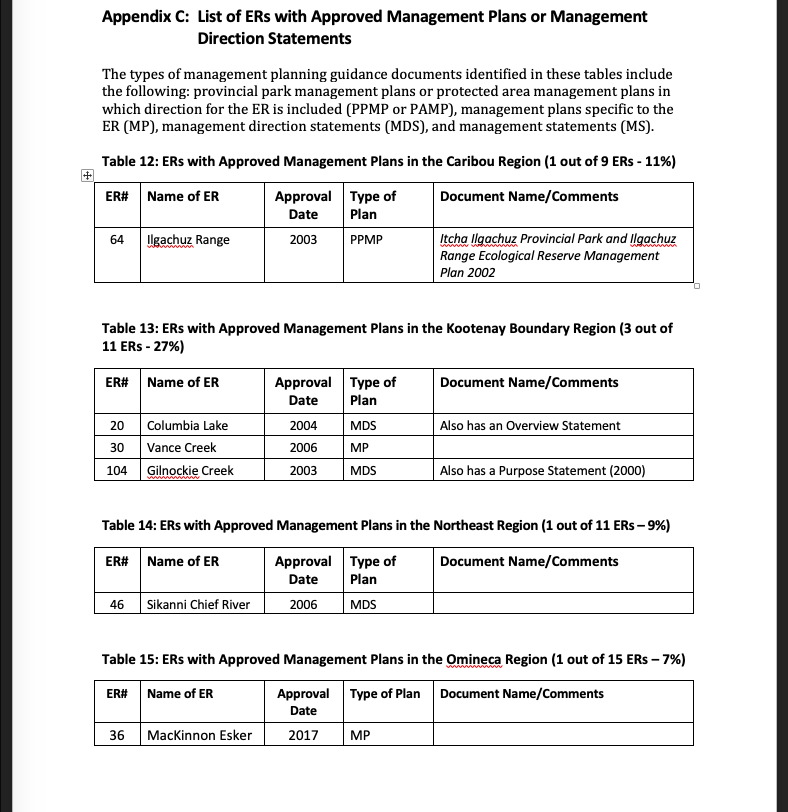

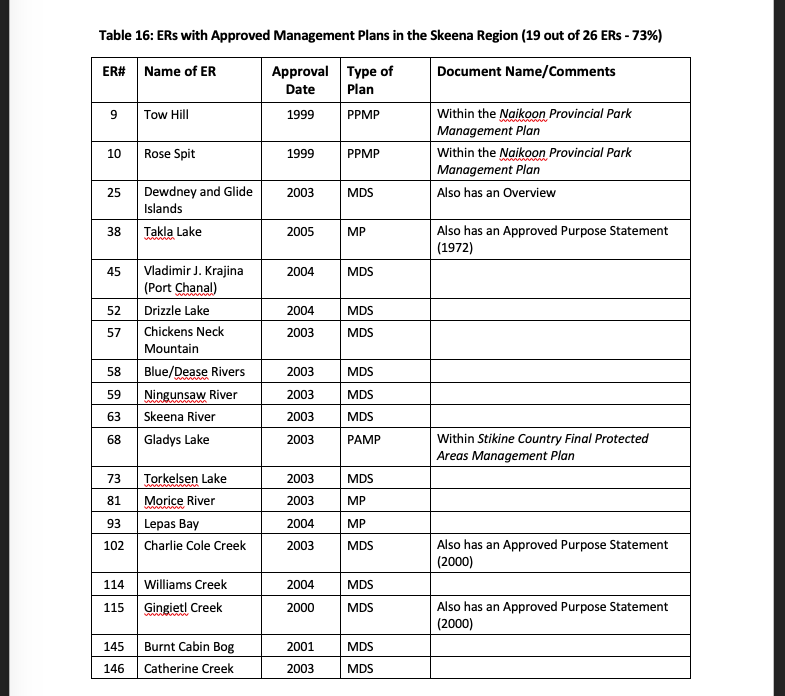

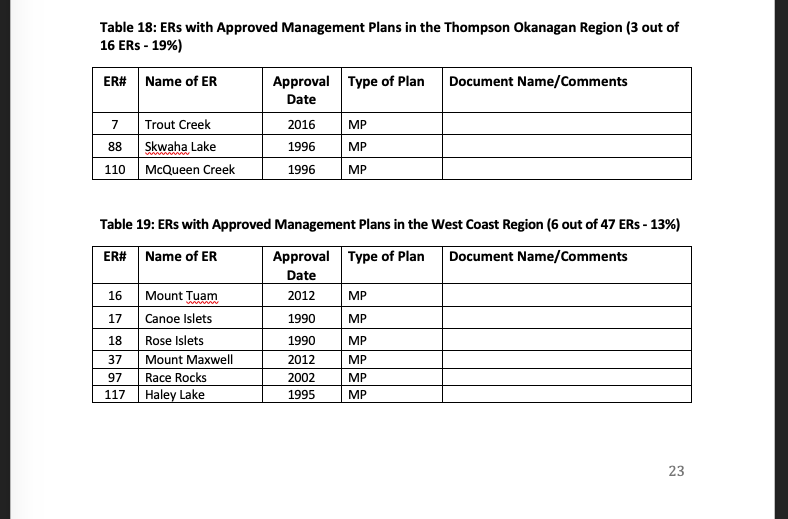

Appendix C: List of ERs with Approved Management Plans or Management Direction Statements

The types of management planning guidance documents identified in these tables include the following: provincial park management plans or protected area management plans in which direction for the ER is included (PPMP or PAMP), management plans specific to the ER (MP), management direction statements (MDS), and management statements (MS).

———————————————————————————–21

————————————————————————————22

————————————————————————————-23

————————————————————————————–24

————————————————————————————–25

———————————————————————————–26

————————————————————————————27

————————————————————————————-28

———————————————————————————31

———————————————————————————-32

———————————————————————————-33

———————————————————————————-38