News/Reports

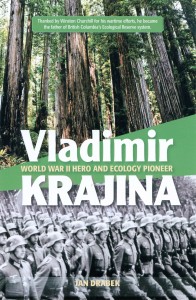

Vladimir J. Krajina World War II hero and Ecology Pioneer

The author, Jan Drabek has provided us with the introduction and chapter 15 of his book on Vladimir Krajina . In Chapter 15, he discusses the origin of the Ecological Reserves Program. The book was published in 2012. It is available from Ronsdale Press.

Introduction

During the war “Krajina” was a just a concept which was not necessarily a man’s name. At least for me, initially. With a small “k” the word in Czech can mean either countryside or an artist’s landscape and since it’s impossible to detect capitals in spoken language, I became thoroughly confused. As a person Krajina is masculine, as a landscape it’s feminine and around our family dinner table it could be used interchangeably. Since I was seven at the time I was not too swift in grasping which was which; my brain merely registered there exists some vague entity by that name. Somewhere.

It didn’t help much that there was another entity bandied around the family dinner table at that time called drtina. In my native language this means material which has been crushed. Same as with krajina, drtina could be either feminine or masculine, according to the context. These mysteries were not explained by my parents: I think it was presumed that the greater the confusion in the minds of their progeny, the less likely my brother and I were to talk about the men named Krajina or Drtina at school.

Because when I first began hearing of these confusing words, Krajina was either hiding from the Gestapo or being imprisoned by it. Drtina was permanently in a London exile, broadcasting weekly commentaries in Czech over the BBC, invariably predicting a sad end for the Third Reich. Both men, now fully materialized, are pictured alongside my father and two other prominent Resistance members in an oft-reproduced photograph of when they met at a Prague airport in May 1945. Drtina was being welcomed from his London exile. For added piquancy, in the background there is a tank with some boisterous Red Army types on it — an ominous sign of things to come.

I began to understand that the apparent landscape my parents referred to during the war was in fact this man with a dark mane which extended in a triangular fashion of a widow’s peak into his forehead. One of my father’s best friends and someone who seldom smiled, Vladimir Krajina was now somewhat larger than life. He was a great national hero who during the war had provided the Allies with some of their most valuable strategic intelligence.

Along with his wife Marie (always referred to in our family as “Mánička”), and their daughter Milena, he took up residence two floors below in our apartment house. Milena was my exact contemporary and a classmate. To complete the Krajina family group, there was a perennially smiling grandmother, Marie’s mother.

It has become morbidly fashionable in today’s Czech Republic to downplay the role of the Czech wartime underground. By way of comparison it is true that perhaps it did not produce such spectacularly colourful personalities as the Norwegian Max Manus or the Yugoslav Tito, but there were some sound reasons for it.

The Norwegian underground came into existence only after the Nazi invasion of April 1940; the Yugoslavian a year later. By that time, having been active for more than two years, the Czech underground had provided some spectacular services for the Allies. Of course, during that time many of its members had been imprisoned and executed.

In wartime there were over 1,000 kilometers of mostly hostile and mountainous terrain between Berlin and Belgrade while the Norwegians, though Nazi-occupied, were mercifully separated from Hitler by an ocean. On the other hand the distance between Prague and Berlin is a mere 280 kilometers and over excellent roads, so it was much easier for the Nazis to keep sabotage and/or partisan activity at a minimum in the Czech Protectorate. However, they were far less successful when it came to controlling intelligence leaks.

The Norwegian resistance hero Manus was also being hunted, but periodically he was able to slip for a breather into neighboring neutral Sweden, where he relaxed and sipped coffee or something stronger with the MI 5 types at the British Embassy. And Tito was surrounded by his fellow partisans in territory effectively controlled by them. He was also supplied fairly regularly via air and sea by the British.

Nothing like that was available to Krajina. By comparison, for nearly two years between 1941 and 1943 with the Gestapo relentlessly hunting him down, Vladimir Krajina was hidden by good people who risked their lives by providing him with shelter. One can imagine the effect such tension would have had on a man less committed. And Krajina not only survived but also effectively led.

In touch with a highly-placed Nazi official during those two years, Krajina and his group were sending radio messages to London about such things as Hitler cancelling his plans for the invasion of Britain, the date of the planned Nazi attack in the Balkans and — perhaps most important of all — the date of Hitler’s invasion of the USSR. Churchill duly informed Stalin but the Soviet dictator, true to form, distrusted any such news emanating from the West. He made no preparations, which cost the Soviet Union several thousand lives initially, millions in the long run.

This writer remembers a group of Czech wartime resistance workers meeting in their New York City exile during the 1950s, and somehow the conversation turned to the 1942 film Casablanca, which featured a supposed leader of the Czechoslovak wartime underground with the Hungarian name of Victor Laszlo. It was played by Paul Henreid, a real-life refugee who escaped from the looming Austrian Nazism.

To a man they had loved the movie, though not as a documentary but as a well-acted fairytale. To start off, the idea of Laszlo, the most sought-after escapee from the Nazis walking about de facto Nazi-controlled Casablanca in a well-ironed white suit while sipping champagne cocktails at Rick’s Café Americain may have appealed to Hollywood mogul Jack Warner, but would have been totally inconsistent with the actions of a true conspirator. By contrast Krajina, the real-life Czech underground leader adopted a different name and grew a beard before he ventured out in public in the remote Český ráj (Czech Paradise) area.

In the film there is a scene in which the Vichy collaborationist police break up an underground meeting and Laszlo escapes with the head waiter from the café, explaining that the police broke up our meeting, we escaped in the last moment. When they detected such meetings in the Czech lands the Nazis always made sure that the area was completely surrounded. On the other hand, the ever-cautious Krajina would never have attended such a meeting anyway. He preferred walks through dark streets and, whenever possible, a one-on-one arrangement.

Perhaps least believable in the film is the incessant clever banter between the Gestapo Major Strasser (who inexplicably wears a dress Luftwaffe uniform!), and the Vichy police chief Renault, Rick and at times even Laszlo himself.

Instead of simply grabbing Laszlo and taking him back to Germany, Strasser bargains with him and when Laszlo refuses to divulge the names of underground leaders throughout Europe, he informs him that it is my duty that you stay in Casablanca. In reality it would have been his duty to either pack him off to Germany or simply have him shot.

On the subject of the European underground leaders in Paris, Athens, Amsterdam and even Berlin, it’s significant to note that Krajina always did his best not to know anyone beyond his closest group of conspirators precisely for that reason: so that under torture he would not have been able to betray them. Also, the Nazis kept a tight control on communications between the various parts of their empire because the creation of anything resembling a European underground network would have spelled a doom for their designs to control Europe.

And when Laszlo tells Strasser that even giving him the names of the leaders would not help the Germans because “from every corner hundreds, thousands would rise in our place “ whom even the Germans could not kill, he is unfortunately sadly mistaken. As Krajina predicted, the assassination of the SS leader Reinhard Heydrich, Deputy Reich Protector of the Czech Protectorate, triggered an unprecedented murderous rampage of the Nazis prevented the underground from ever again repeating its successes.

And speaking of the Heydrich assassination, just how naively the Americans initially saw the European resistance is evident in a 1943 Hollywood film called Hangmen Also Die. In it, after letting a group of students go without checking a single identity, a Prague university professor is arrested by the Gestapo and he asks: On what charge?

Krajina, who must have seen many a bloodied body brought to the Gestapo headquarters during his incarceration, would have probably produced a sad smile. Especially after Heydrich’s death, those arrested wouldn’t have dared to ask anything. The standard procedure was to stand facing the wall while the Gestapo thoroughly ransacked your apartment.

But there is one scene in Casablanca with which not only Krajina but quite likely every resistance member would agree. It comes when Rick, while bandaging Laszlo’s injured hand, asks Laszlo if he had ever wondered if it’s worth all this.

“You might as well question why we breathe. If we stop breathing, we will die. If we stop fighting our enemies, the world will die,” is Laszlo’s answer.

In a way Vladimir Krajina’s career was reminiscent of a character in Walt Disney’s prize-winning 1938 cartoon called Ferdinand the Bull. It tells of a magnificent animal chosen for the bullfighting ring. But the gentle bull prefers to smell the flowers instead of fighting and eventually, after failing to engage the toreador, is returned to his pasture. According to the narration, “he’s sitting there still, under his cork tree, smelling his flowers quietly. He is very happy.” The same way Vladimir Krajina was happy under his beloved Douglas firs in British Columbia, with perhaps one Disneyesque factor added: all his life the botanist Vladimir Krajina suffered from hay fever.

The flower-loving resistance fighter may have been a thorn in the Germans’ side, but unlike many of his compatriots, he refused to carry a gun. And – also unlike many of them — he survived to smell many more flowers.

For four years Krajina was either on the run or engaged in a dangerous chess game with the Gestapo. Every move he made, however slight, was dependent on the lives of numerous people. It was utterly exhausting both physically and mentally, yet nothing could thwart his determination. Even the Allied victory in 1945 did not bring the relaxation and complete return to his beloved botany which he craved so much. There was now a new enemy in the form of yet another madman. This time his name was Stalin.

In 1948 the Krajinas and the Drabeks took a winter vacation together in the Orlice Mountains. Shortly after New Year Krajina, his daughter Milena, my father and I, climbed on skis to the top of the 1400 metre high mountain, Kralický Sněžník. We had lunch there and then started to make our way down via another route.

Soon it began to snow and with the wind up it was obvious a blizzard was coming. In the middle of the woods we suddenly came upon a creek which had overflowed its banks and had been transformed into about a five meter-wide sheet of ice. What followed was proof of Krajina’s uncanny ability to deal successfully with emergencies in his own ingenious way.

It was obvious, due to the storm and approaching darkness, that we couldn’t return to the hotel where we had lunch. But going forward and crossing the icy strip which extended down into the steep valley could be equally dangerous. While the rest of us despaired in helpless indecision, Krajina assessed the situation, and then swiftly took command, ordering us to take off our coats and tie them together. Grabbing one end of them, he lay down on the ice and inch by inch nudged himself to the other side, holding on to his metal tipped ski pole with his other hand. With the aid of this improvised coat-rope which we held on to for dear life, his daughter Milena and I then followed his example, with Krajina on one side and my father on the other. The last one across was my father, following Krajina’s example with the ski pole as a brake in case of a possible slip-up.

This quick-witted ability to creatively and quickly solve difficult problems ranked right up there with Krajina’s incredible survival instinct. Again and again it manifested itself during his dealings with the Nazis and Communists.

Mere months after the frozen stream episode he, like us, escaped to neighbouring West Germany, following the February Communist takeover of Czechoslovakia. There we were briefly interned with him in a Frankfurt refugee centre.

I did not see Krajina again until I arrived in Vancouver in the mid- 1960s. By that time he was not only well established in the botany department of the University of British Columbia, but was also an important advisor to the provincial ministry of forests and the forest industry as a whole.

The circumstances of his life may have changed, but not his boldness and determination, also loyalty to his friends and, in my case, loyalty to their progeny. I was toying with the idea of graduate studies in humanities during the 1960s, though my undergraduate grades were not that encouraging. The UBC department in question was not enthusiastic about admitting me, but Krajina knew very well that with a department member vouching for an applicant, the situation could change. He approached a Czech student who had once spent a considerable time at Krajina’s house and was now a junior member of the department in question — to ask him to present my case as my sponsor. The timid man begged off, explaining that it really wasn’t the proper thing to do, making all sorts of excuses which Krajina found frivolous. It was obvious that the young professor was not about to risk his career just because it concerned a fellow Czech.

That, of course, was inimical to Krajina’s conviction that when it concerned the fate of any countryman anywhere a true patriot must be ready to place his arm into the fire for him. I recall him sadly informing me that nothing could be done and at the same time leaving no doubt as to what he now thought of his young protégé, whom up until then, he considered a friend.

Fast forward about eight years. My first novel had been published in Toronto both in its original English and in a Czech translation. The reviews were exceptionally good and I was resting on my laurels quite comfortably.

Then along came a phone call from Vladimir Krajina who had just finished reading it. Though now a patriotic Canadian, he still considered America to be a beacon for the free world and didn’t like my frequent criticism of the U.S. in the novel. In his merciless opinion some of the chapters of the novel could have been easily published in the Czech Communist Party newspaper Rudé Právo — to help with its anti-American propaganda.

Thinking about it now, almost 40 years later, I have come to the conclusion he may have been at least partially right. My intent had been to show how newly arrived, idealistic immigrants were sometimes unable to cope with America’s idiosyncrasies, even blemishes. And for dramatic purposes I may have overstated them.

But this was classic Vladimir Krajina, unabashed, undeterred and unafraid of offending people when it came to stating what he believed to be the truth. And by critiquing the work of a first-time novelist in his thirties, who also happened to be the son of his good friend, Krajina quite likely considered the call to be of an educational nature. After all, he was a professor with impeccable credentials, even though these were hardly in literary criticism.

Krajina straddled two different worlds during two different ages. More than half of his life had been spent in the West, which had provided him with the greatest freedoms possible, while his wartime experiences in Czechoslovakia had resulted in personal restrictions that were hardly imaginable.

He was born into a pre-World War I Central Europe in one of the most prosperous corners of the sprawling Austro-Hungarian Empire. It was a sleepy corner with its all-powerful emperor already seventy-five years old, which was an enviable age at the time. As a result, when steam engines were the norm and the first airplanes were taking to the air, his lands were run according to the horse-and-buggy customs of early nineteenth century. Austria-Hungary was actually more comatose than sleepy. The first Czechoslovak president Masaryk estimated that his country would need fifty years for democracy to grab permanent hold. At the time of the Munich Agreement his country was barely twenty years old.

But Krajina adapted well. And many times. He may have never fully mastered the Queen’s English (though some claim that he succeeded in transforming it into Krajina’s Own), but he certainly understood the spirit of Canada, its requirements and his duties. At the same time he contributed his bold forays in quest of truth and his valiant attempts to do the right thing.

Many of his “straight arrow” ways may have seemed an anachronism in this screamingly imperfect world. Perhaps they were. But to be certain that men of his ilk are now out of place, we would need a far more convincing proof of it than we are presently able to muster.

Chapter Fifteen

In 1970 came Krajina’s supposed retirement from the university. In reality he was at best only partially being freed from the burden of regular lecturing and from supervising graduate students, that was all.

And there were other, fairly sizeable fish to fry.

Without Vladimir Krajina it is highly unlikely there would have been in this province an institution such as the ecologogical reserves. Certainly not during the 1970s. British Columbia would not have been a pioneer in this endeavour. Along with his mapping of its biogeoclimatic zones, the Ecological Reserves of British Columbia were Krajina’s enormous contribution to the environment of this province. Among those who have put this province on the map they rank right up there with George Vancouver’s exploration of the coastline and Alexander McKenzie’s crossing of the North American continent.

Granted that Krajina’s feat does not at first seem as pioneering as Vancouver’s. It did not provide an image anywhere near as dramatic as the good captain on the deck of his ship with a telescope to his eye, sails fluttering above and native canoes full of natives suspiciously watching the scene from a respectful distance.

Or that mountain of energy called McKenzie, chopping his way through the dense forest until he pushed the last batch of brush aside near Bella Coola. And suddenly there it was – the blue ocean he had been searching for so long, then happily painting his Alex MacKenzie, from Canada, by land, 22nd July 1793 on a nearby rock.

If Krajina had travelled to Clayoquot Sound near Tofino 178 years later, he too could have scribbled his name on a rock there, saying Vladimir Krajina, father of many ecological reserves of which this is the first. It was established due to its great diversity of seabird colonies. Except that by then he was too busy, filling out tedious applications for other reserves, meeting with politicians, bureaucrats, ecologists and journalists. Doing anything that would bring the idea of such reserves to the public eye.

Here was not a dramatic sight at all, with Krajina and his students sloshing through the rain forest, examining, mapping, evaluating and then, back in his UBC shack, proposing — mostly tedious chores, not at all triumphant or even dramatic.

At the end of each year Krajina sat down to write a report on the work of the ecological reserves committee. He wrote it but you won’t find a word about it in high school history books, which are usually made of more colourful stuff.

Already in the fall of 1969 Vancouver newspapers reported that a GROUP LAYS GROUNDWORK FOR UNDISTURBED TRACTS. It quoted Krajina a botanist who is heading a group of scientists interested in the program, that British Columbia leads in Canada and most parts of the world in its establishment of ecological reserves.

The article appeared almost two years before the actual passing of the Ecological Reserve Act by British Columbia Legislature. But in the article the highly confident Krajina stated that European ecologists would be most gratified if they could recover lands in their virgin state. We fortunately have some parts of the province where we do not have to spend money to recover the different types of ecosystems.

In the spring of 1979 ForesTalk Resource Magazine provided the public with this succinct introduction to the reserves:

One of B.C.’s most spectacular forests, a Sitka spruce stand near Port Chanal in the Queen Charlottes, will never be logged. Nor will man ever interfere with the rare Mara Meadow orchids near Salmon Arm, or the Stone sheep habitat at Gladys Lake on the Spatsizi Plateau. These sites, and 90 others like them, occupy a special position in the province. They have been set aside as ecological reserves. You won’t see them advertised anywhere; they aren’t marked on any tourist map.However, although a few very fragile reserves are accessible to the public only by special permit, the rest are normally open for such uses as hiking, bird watching and photography, as well as for their prime uses – research and education.

But why go to all the trouble of carefully setting aside these particular parcels of land? Because in each reserve there is something important to preserve. In some cases the special feature is a unique plant, animal or landform; more often it is entire ecosystem typical to a particular region – a complete system of plants, animals and their environment.

In his 1975 progress report on the ecological reserves Krajina mentioned that being prompted by British Columbia, Quebec, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, and New Brunswick have already passed or are about to pass their own ecological reserves acts.

At leat temporarily he cast aside any latent prejudices he might have still harboured in stating that both B.C. and the Soviet Union showed good planning on the ecological reserve front. But then, in typically Krajina-belabored English, he couldn’t resist a jab at a power which for the past eight years had occupied his native country:

This very high rate in one free society with full political freedoms, where everything develops slowly with participation of all people concerned, and in one country controlled by a dictatorship operating easily with the short-cuts which do not allow any opposing views, are rather a great stimulation for our work in which we cannot become idle or tired or satisfied with any partial success.

In the document Krajina mentioned the passing of the 1971 Ecological Reserve Act by the provincial legislature. However, the effective starting point for his ecological reserve campaign should have really been predated by six years, to November 25, 1965. On that day in Victoria several academics plus an official from the Provincial Museum met with Ray Williston, Minister of Lands, Forests and Water Resources.

Williston was informed about the need for the creation of ecological reserves in British Columbia; he was also told that this action was strongly supported by the International Biological Program in which Canada was a leading participant.

The minister was basically in agreement and promised to brief other members of the provincial cabinet on the project. He was handed letters of support from the visiting delegation with reasons given for the need:

Conservation of all kinds of natural environmental conditions (is) imperative for survival and maintenance of large heterogeneous natural gene pool of different organisms, went part of the reasoning, but with a hint of editorializing, it could’t resist noting: This is particularly necessary in a world whose current tendencies are to simplify, modify, and destroy all that is not immediately useful to man.

The concluding sentence of that paragraph constituted a bit of a bait for the Social Credit Government of the day, which was usually much more responsive to proposed economic stimuli than to the academic kind. And it was certainly never averse to the idea of leaving a larger imprint on provincial history:

The diversity of life in the natural biogeocoenoses and their biogeoclimatic zones is a national and international treasure which should remain available forever.

Exactly a year later an organization with a mouthful of a name Terrestrial Communities Subcommittee of the Canadian Committee of the International Biological Program met in Victoria. Consisting of elected government officials and representatives of provincial government departments plus the academics, it laid important groundwork for the idea of ecological reserves.

Early the following year Krajina chaired a Vancouver meeting of 29 prominent scientists who were informed of the survey work about to be taken, with an eye leading to the establishment of the reserves. The work was completed a year later, when Williston and W.K. Kiernan, Minister of Recreation and Conservation, agreed with the formation of the British Columbia Government Ecological Reserves Committee.

Krajina was named one of the co-chairmen of the committee with the right to co-opt other scientists who would activly participate in the work of ecological reserves. In his report on the subsequent meetings he reported that 20 to 50 people were now usually present at the meetings as interest in the reserves grew.

Early in 1971, during the throne debate at the Victoria legislature, Williston presented the results of several years of study and announced that an Ecological Reserves Bill would be presented during the upcoming session of the legislature. It was duly passed in April.

Not everyone in private industry or governmental circles fully understood the function of the proposed reserves. Alistair Crerar, Director of the Government Land Use Committee Secretariat, suggested including former garbage dump sites among the proposed ecological reserves.

…To which Krajina patiently explained that of primary interest to those proposing the reserves was to find out how nature operated normally without human beings.

But in the end Krajina was elated with the passage of the bill, though there must have been some who were not. Section 5 of the bill stated that any area designated as an ecological reserve would automatically be removed from disposition as granted under other act such as Land Act, Grazing Act, Water Act, Mineral Act, Placer-Mines Act, Coal Act, Petroleum and Natural Gas Act, Water Resources Act, or Mines Rights-of-way Act.

From that wording one would assume that the Ecological Reserves Act’s needs would automatically push aside any other proposed use of selected land, but such was was far from the case. Before the year 1972 was over Krajina had a thick folder of correspondence from D. Bothwick, Deputy Minister of at the provincial Ministry of Lands, Forests and Water Resources.

In essence, these were rejection slips with which all authors are thoroughly familiar. But while the literary kind often proffer the mysterious claim that the sent manuscript does not fit into the publisher’s program, (whenever a suspected bestseller had been sniffed such programs had been known to be instantly altered), Krajina’s ecological rejection slips were never that vague.

For example his proposal for an ecological reserve No. 93 at Chewhat Lake and Climax Forest had been rejected not only because it encompassed several outstanding mineral claims, but because it also lay within an area to be included in the proposed Pacific Rim National Park.

And up north, Proposal No. 82 at Murray Range near Pine Pass was in conflict with Amoco Canada’s natural gas permit.

The wording of the rejection of Krajina’s Proposal No.76 at Morfee Lake within the Municipality of MacKenzie was even more blunt, stating that the acreage requested was far too ambitious and because the land requested was required by the local community for recreation. As an extra added reason for the rejection slip Bothwick noted that, among others, the proposal was strongly objected to by Takla Forest Products Ltd, Peace Salvage Association and The District of Mackenzie…

Proposal No. 74 at Becker’s Prairie was turned down because:

a. a major part of it was within the boundaries of Government of Canada’s terrain used for military purposes,

b. it was used for grazing of 2,700 head of cattle from four local ranches and

c. It was heavily used by waterfowl hunters in the fall.

Proposal No. 31 for the Kerouard Islands, part of the Haida Gwai archipelago, was rejected because since 1916 the islands had been reserved by the Federal Department of Transport.

Some proposals had been rejected simply because they had natural gas potential, others because it was questioned whether they really had the potential for hydrological studies as stated in one proposal. And Proposal No. 70 for the Horsey Creek in the Mc Bride Area reserve was not accepted because no outstanding dense stand of Western Red Cedar was detected in the area as claimed by the examining surveyor. In other words, even the accuracy of Krajina’s team’s research was on occasion being questioned.

In 1972 Krajina proudly reported that he spoke about this excellent environmental development at scientific meetings in Greece, India, Indonesia, Jamaica, and Australia. Everywhere the message was greatly applauded because of the great foresight by the British Columbia Provincial Government.

Such was the good news. But there was also the bad kind:

However, certain very important ecosystems to date could not be covered by the new Ecological Reserve Act because they are no longer in Crown lands…It is necessary to preserve them as soon as possible, if we wish to prevent their possible total destruction.

It wasn’t always possible but by 1972 there were 43 ecological reserves in sizes from 0.6 hectares to 6,212 ha in existence. The previous year Krajina had presented his progress report at what to this day counts as the grandest provincial gathering of notables concerning the reserves. Arranged by Leon Koerner, it was attended by the chancellors of Simon Fraser and UBC, the president UBC and a representtive of the University of Victoria.

Those guests were to be expected. Somewhat surprising, however, was the presence at the progress meeting of a representative from the Council of Forest Industries of B.C. as well as that of the British Columbia Forest Products, Ltd. What’s more, a year later Krajina was made fellow of the Institute of Forestry of Canada.

In 1975 he told a botany seminar at UBC that there were now 59 reserves covering 104,073 acres, while 235 proposals have been presented to the government so far although we don’t expect that out of every proposal we’ll get a reserve.

Krajina then critisized the fish and wildlife branch of the provincial government for opposing a proposal for the Toad Hotsprings reserve, site of a natural saltlick which attracted largenumbers of animals.

It’s very disappointing, he said. These are the people who should be proposing the area (for a reserve) on their own.

Krajina explained that animals approaching salt licks are docile and easily approached. Hunting near them should not be allowed.

When the Vancouver Sun reported on the seminar, Krajina responded with a letter, saying it should be stressed that the proposed reserves include not only lands with rich and fertile soils but also those with low or even negligible productivity because they too needed to be preserved.

In the same letter he corrected the newspaper’s statement that access to the reserves was limited to authorized persons, saying that there is no intention to do so. However, strict observance of the following general regulations should include no camping (except perhaps with special permission), no fires and no destruction of natural phenomena.

The general tone of the letter showed that by now Krajina was well aware the press was generally on his side and he praised the paper for informing the public about efforts to preserve parts of the province in its natural state.

At present the number of ecological reserves in this province continues to grow, albeit much more slowly than in Krajina´s time. In 2011 there were 148 of them. None approved during the last 12 years is anywhere near in size to Gladys Lake Reserve, created in 1975 on the Spatsizi Plateau with its 48,560 hectares. Or the Checkleset Bay Reserve on Northern Vancouver Island, created in 1981, measuring 36,650 hectares.

Nowadays The Ministry of Environment spokesman informs rather lethargically that at present the average size of a reserve is 1084 hectares and that unlike at the onset there is no single person specifically in charge of the reserve program. As to why the growth of the system has lately achieved a snail’s pace the government’s answer is a rather ambiguous statement that the land use planning process is nearly done.

A somewhat clearer statement comes from one of Krajina’s students who later became a member of the Ecological Reserves Board, Dr. Bruce Fraser. Here is his assessment of the reserves’ history;

In the early years, his (Krajina’s) lobbying of government was extensive and insistent. Government barely understood the scientific rationale for large reserves but his persuasiveness prevailed. Later, the bureaucracy, heeding economic signals from senior government derived from successful lobbying by industry, progressively minimized the size of reserves. They tended to become postage stamps of rare species and plant associations rather than the significant scientific benchmarks that Vladimir believed were necessary for the long term understanding of the productive forest on which a healthy industry was based. The contest was always about losing immediate logging opportunity vs science for the long term. One of his most famous cautionary public lectures began with “I see Vancouver a ghost town”…as he went on to explain how much of the city depended on the health and productivity of the forest and its industries and the ultimate dangers of failure to learn and conserve.

There were various specific reasons for settiing up reserves. Among the most bizarre of them is the combination of Ponderose pine site combined with a rattle snake den which can be found at the Kalamalka Lake reserve near Vernon. Needless to say, here access to it by the public is limited by nature itself.

A more romantic raison d’etre is offered by the San Juan Ridge Ecological Reserve east of Port Renfrew on Vancouver Island, which boasts a of a profusion of the rare white avalanche lili, or, as Vladimir Krajina would say, Erythronium montanum. There is also the Skagit River reserve with its stand of Pacific rhododendrons or – still speaking of romance — the Byers/Conroy/Harvey/Sinnet Islands at the Hecate Strait, which is an important seabird and marine mammal breeding area.

The largest reserve, Gladys Lake Ecological Reserve on the Spatsizi Plateau, there are stone sheep, mountain goats and caribou along with their environment. And while the Chasm reserve near Clinton features ponderosa pine at its northern limit, the Checkleset Bay Ecological Reserve provides habitat for the province’s prime sea otter population.

Other reserves preserve breeding colonies of herring and ring-billed gulls, native oysters, endangered Vancouver Island marmots, the most arid ecosystem in Canada, adders tongue fern, well-developed lichen communities or a stand of Garry oaks. In the Kootenays there is the fairly large Lew Creek Ecological Reserve which is unique by preserving three biogeoclimatic zones in the same drainage basin.

…And there may be some with more hidden reasons for their existence. When Krajina during the early seventies arrived on an island off Horseshoe Bay to examine a proposed reserve, the student with him was somewhat wary. The idea of creating a reserve of fairly common Douglas fir in the dry subzone of a western hemlock was unusual to say the least and could have been a scheme of some well to do local residents to create a buffer zone between their properties and the rest of the island. Despite the the suspected bad omen of Krajina dislocating his ankle while examining the landscape, the result was reserve number 48, the Bowen Island one, closest to Greater Vancouver.

In 1973 came the establishment of the Vladimir Krajina Ecological Reserve on Haida Gwai, which at the time was still Queen Charlotte Islands. A windy, storm-prone place in the Port Chanal vicinity of the western side of Graham Island, it extends from the coast to the majestic ridges. At one point the terrain rises to 825 meters with steep slopes facing the inlet while moderate to flat terrain exists elsewhere.

It’s a classic ecological reserve location, a genetic bank of rare as well as common species. Calling it a benchmark ecosystem, a booklet of the Friends of Ecological Reserves goes on to say: Here is an outdoor museum and laboratory available for botanical, wildlife, geographical fishery, forestry and ecological research.

As memorials go, this is a good one. Accessible only by boat or float plane, the reserve consists of 9,734 hectares with abundant and varied fauna and flora.. In other words, it is one of the larger and more varied ones within the system. Located on the west west coast of Graham Island, it includes 60 kilometers of marine shoreline to large islands and a fjord at Port Chanal. There is one relatively large body of fresh water called Mercer Lake, and several smaller lakes on Hippa Island. The entire watershed of Mace Creek plus several minor creeks are also part of the reserve.

Krajina must have loved its old growth coniferous forest and mossy underlay of the reserve with luxuriant almost pure stands of Sitka spruce. But there are also barren headlands, meadows, bogs and alpine habitats

which extend to unusually low elevations.

The reserve has abundance of liverworts and mosses which Krajina, being the avid bryologist, must have appreciated as well. In fact some 130 species of higher plants exist on the reserve, many of them endemic to the islands or provincially rare.

Among the bird population, significant colonies of Ancient Murrelets, Cassin’s Auklets and both Leach and Fork-tailed Storm Petrels inhabit the reserve. Also present are Bald Eagles and Peregrine Falcons. The Queen Charlotte subspecies of Northern Saw-whet Owl, Steller’s Jay and Hairy Woodpecker make their home within the reserve and about 300 Steller Sea Lions use Hippa Island as a winter haul-out.

The Mercer Lake system is crucial to eight thousand Sockeye Salmon with Coho, Pink and Chum Salmon also present.

But all is not well within the remote Vladimir J. Krajina Reserve, with climate change being considerd the greatest threat to its abundant nature. Habitat loss due to raised sea level and increased storm activity along the already stormy shoreline posing a threat to the shorebirds’ nesting habitats.

The expected warming of the sea and with it changed patters of runoff fom the island pose another threat along with possible drought conditions.

Other threats are posed by commercial fishing, poaching, logging activity in the neighborhood of the reserve which endangers the Sockey Salmon. Also preying raccoons, and even flight traffic disrupting the seabird’s nesting habits.

But at present these are merely threats, many of which are faced elsewhere in the province and throughout the world. One is fairly certain that all in all Vladimir Krajina would have been happy with the pristine reserve that bears his name

With all his efforts around the research and lobbying on behalf of the reserves, Krajina still found time to actively oppose the scheduled visit to Vancouver of the Soviet Premier Alexei Kosygin, who had earlier been assaulted in eastern Canada by a Hungarian exile. The day before his visit in 1971 some two thousand demonstrations marched through Vancouver with placards. Krajina was in the forefront. The Vancouver Province had published a letter, in which Krajina in his inimitable style advises the premier what do:

He should introduce in Soviet Russia and countries under Soviet control the only democratic way for self-determination, i.e. by free voting to decide where and under what political regime they wish to live. Such free voting should be under the supervision of the United Nations.

The letter was signed by him as President of the Vancouver Chapter of the Czechoslovak National Association.

There was no reaction. Despite his advice, sadly the Soviet Union did not manage to dissolve itself until twenty years later. But there was at least one tangible result: The film Russian Roulette was based on the novel Kosygin is Coming by the Canadian author Tom Ardies. The movie, released in 1975, had the distinction of having Louise Fletcher in it, who won an Oscar that year. Alas not for Kosygin, which was called a violent, unsatisfying thriller, but for a much better flicker called One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. The director, the Czech-born Miloš Forman, got one too.

Krajina’s foray into politicised economics was equally unsuccessful. in an article in the Vancouver Province a year later which tore into labour unions under the title HOW CAN WE TOLERATE THIS STRIKE EXTORTION?

In it , he opined that we were living in a hyperdemocratic status, which dangerously approaches anarchy, then went on to establish the principle that while almost everybody wanted to get higher wages or salaries that would mean a better standard of living, almost nobody cared what the result would be. That result, according to him, would be constant inflation.

Governmental control of income and prices can be done justly for all concerned…Such governments will be solidly backed by all good common sense people who will unite when requested to do so.

It was an interesting thought from a man who had suffered government control in the hands of two extremely powerful totalitarian regimes. But he did mention that his solution applied only to those governments which were democratically elected.

Elsewhere in his writings Krajina defended the idea of private enterprise in forestry, hinting that competition guaranteed no company would become excessively powerful. But obviously, according to him, this principle should not be applied indiscriminately. It should be remembered that he had been the general secretary of the Czechoslovak National Socialist Party.

The article may not have been particularly well constructed, but it did once more indicate Krajina’s undying faith in the innate human goodness. Despite his own, personal experiences if only given a chance, Krajina seemed to believe, the individual would do the right thing.

The decade was the time for many accolades and honours to be lavished on Krajina. In 1970 came the Northwest Scientific Association’s citation for outstanding work in northwest ecology and in 1972 came the Lawson Medal for a Lifetime Contribution to Botany in Canada from the Canadian Botanical Association. A year later came his first honorary degree. Inscribed in Krajina’s beloved Latin, it was in law (of all things!) and came from the now defunct Notre Dame University in Nelson, B.C. In 1979 The National Film Board made a movie about him entitled The Forests and Vladimir Krajina.

Also see the FIle on Vladimir Krajina Ecological reserve

And the File on Vladimir Krajina