News/Reports

Why Comox Bluffs ER Contains Out-Of-Range Plant Species

From: THE LOG • FRIENDS OF ECOLOGICAL RESERVES NEWSLETTER • SPRING 2005

by Chris Pielou

Comox Bluffs ER (47 ha), in the Comox Valley, Vancouver Island, is home to a number of interesting plants, which is why the Reserve was established (on April 30, 1996). Four of its botanical treasures are rare, blue-listed species, defined by the BC Conservation Data Centre as species of “special concern”. These are:

Comox Bluffs ER (47 ha), in the Comox Valley, Vancouver Island, is home to a number of interesting plants, which is why the Reserve was established (on April 30, 1996). Four of its botanical treasures are rare, blue-listed species, defined by the BC Conservation Data Centre as species of “special concern”. These are:

- Least moonwort, Botrychium simplex, one of the grape ferns;

- Macoun’s groundsel, Senecio macouni;

- Dune bentgrass, Agrostis pallens;

- Western St. John’s-wort, Hypericum scouleri.They were observed there several years ago by Adolf and Oluna Ceska, Hans Roemer and Betty Brooks; it’s to be hoped they are still there, but so far, after one summer as the ER’s warden, I have seen only the Hypericum.

Five other plants worth noting and protecting belong to species growing in outlying fragments of their main ranges. They are:

- I American wild carrot, Daucus pusillus, a miniature version of Queen Anne’s Lace to which it is closely related. In BC it grows only near the east coast of southern Vancouver Island, plus the Gulf Islands and adjacent mainland.

- I Hairy manzanita, Arctostaphylos columbiana. It hybridizes with its close relative kinnickinnick where the two grow close together, producing hybrids known as Arctostaphylos X media which are obviously intermediate between their parents. They grow over much the same range as American Wild carrot and also in western Vancouver Island.

- I Rocky Mountain juniper, Juniperus scopulorum, which is common in the Interior and the Rockies, and also along the east coast of VI and the Gulf Islands. It grows in Helliwell Park on Hornby Island, as well as on Comox Bluffs.

- Narrow sword fern, Polystichum imbricans. In BC this fern grows only in southern VI and in the southern part of the Fraser Canyon.

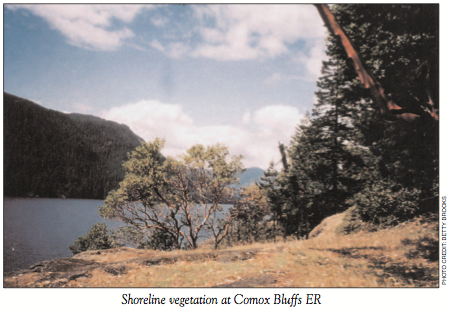

What these species have in common is their habitat. Their main ranges in BC are parts of the province with hot summers and with extensive dry, grassy, rocky lowland areas. The Comox Bluffs, although surrounded by wet raincoast forest, provide a small, outlying area of suitable habitat because of their geological origin.

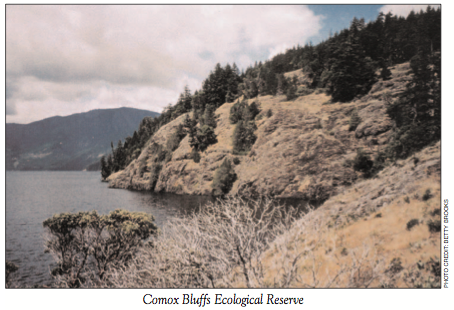

As you enter the ER at its eastern end, along the shore of Comox Lake, the first part of the walk is through shady Douglas-fir forest, beside a wide sandy beach. Not until you’re half way through the ER does the scene suddenly change. Down at lake level, the beach ends abruptly to be replaced by a rock precipice rising steeply from the water. Inland from the shore, the gently undulating, low-lying forest gives way to steep rock bluffs. From cool shady forest you emerge onto hot sunlit slopes (weather permitting). The bluffs face south and because of their steepness, the sun’s rays at midday in summer strike them almost at right angles. Not surprisingly, they are hot and dry for much of the summer.

Now for the geological difference that accounts for the conspicuous contrast between bluffs and forest: The bluffs consist of ancient molten magma, now hardened to basalt and forming the Karmutsen formation. It was extruded as lava from long cracks in the mid-ocean ridge on the sea floor about 250 million years ago (Triassic), when Vancouver Island was at the

bottom of the ocean far out in the Pacific south of the equator. This happened long before the shifting tectonic plate on which it lies had moved up to, and latched on to, the North American continent. The forest immediately east of the bluffs grows on much younger, sedimentary rocks, chiefly, sandstone, laid down under the ocean about 80 million years ago (Cretaceous). The sandstone is softer and much more easily eroded than the basalt, and as a result, the surface of the forest floor overlying it is now low and undulating and the adjacent lake beach wide and sandy. The basalt, in spite of its much greater age, has withstood erosion. Its weathering has produced only a small amount of dust and grit, the first-formed ingredients of soil, and much of what is produced is quickly washed away by winter rain, over the steep, smooth rock. Hence the thin soil.

This explains the botanical contrast between the forest and the bluffs. It is all a matter of geologically-determined habitat. The bluffs are as hot and arid as the southern Gulf Islands, the southern Fraser Canyon and much of the southern Interior, and for that reason these areas have some plant species in common.

This explains the botanical contrast between the forest and the bluffs. It is all a matter of geologically-determined habitat. The bluffs are as hot and arid as the southern Gulf Islands, the southern Fraser Canyon and much of the southern Interior, and for that reason these areas have some plant species in common.

It would be interesting to know how the Comox Bluffs acquired the five “rocky bluff” species listed above. Either their seeds (or spores in the case of the sword fern) chanced to blow in on the wind from their distant mainland territories, which seems most unlikely. Or they migrated northward with all other plants as the ice-sheets of the last ice age melted back twelve or thirteen thousand years ago, exposing bare ground waiting to be occupied. These five particular species could only migrate through, and settle in, hospitable habitats – places where the summers are hot and dry. The steep south-facing slopes of Comox Bluffs are baked by the sun all through hot summer days, and rain, when it falls, drains away quickly over the smooth, steep rock. It is because of the bluffs’ geological characteristics that these plants grow in the Ecological Reserve.

Chris Pielou is volunteer warden for ER 136, Comox Lake Bluffs.